The Origins of Printing in the Czech Republic

Whilst conducting research on incunabula and learning about how book printing originated, the question arose in my mind of the history of printing in Czech Republic, my homeland. The vast majority of the incunabula I had conducted research on were printed in Venice and mostly Western cities, and less so in Eastern Europe, although one must assume that printing was developing there as well. After conducting a literature review in this area of research, it becomes evident that the beginnings of printing in 15th century Czech Republic are vastly focused on editions of the Bible. Thus, the present text investigates Czech Republic’s shift from handwritten to printed books in the late 15th century, beginning with the Bible.

Petr Voit from the Institute of Czech Literature of the Academy of Sciences identifies a gap in this area of research, arguing that early printing in Czech Republic has only been investigated in terms of theology and translation, and that topics of publishing and typography have been minimally researched. Voit’s paper titled “České tištěné Bible 1488–1715 v kontextu domácí knižní kultury” [Czech printed Bibles 1488-1715 in the context of the domestic publishing culture] provides unprecedented and contextualised insight into how printing initially began to develop in the country.

Diffusion of the Movable Type Printing Press [my emphasis on Czech Republic] from Jeremiah E. Dittmar; “Information Technology And Economic Change: The Impact Of The Printing Press.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 126, no. 3, MIT Press, 2011, pp. 1133–72.

To begin with, the economical state of the country at the time plays a significant role in its’ printing development. Voit discusses the economic demands of the process of publishing and typography, and draws a connection to the fact that eighty percent of all Czech Bible editions are reprinted. Furthermore, Czech printers and printing presses were not able or willing to invest large sums of money into these processes if the profits were too delayed. As a solution to see the profits from printing earlier, the Bible was often divided into smaller, separate editions of The Book of Psalms and The New Testament, and even one instance of The Old Testament.

Voit states that printing of the Bible provides a valuable measure of the country’s publishing industry as it was originating, since it dominated the production and demand of the book market (478). Solely looking at production of the Bible, a vast difference is found in comparison to Germany, the neighbouring country to the west. More than 190 German editions of the Bible were produced throughout the 16th century, in comparison to the nine Czech editions (Voit 478). This is further supported by considering that 90 printing presses in Germany were producing Bibles, whilst Czech Republic only had four printing presses to do so. Notably, Germany and other Western countries first printed the Bible in Latin before switching to translated editions, and thus many Latin Bibles were imported into Czech Republic where the domestic presses could not compete. Furthermore, the domestic literary culture at the time is not clear cut or schematic, and mostly consisted of confessional letters and prayer sheets; the new publishers of Biblical texts were thus forced to cater to a wide audience in the demand-driven market. It is thus not surprising that the Czech publishing industry began at a much smaller scale compared to Western countries, but its developments in printing are still worth investigating.

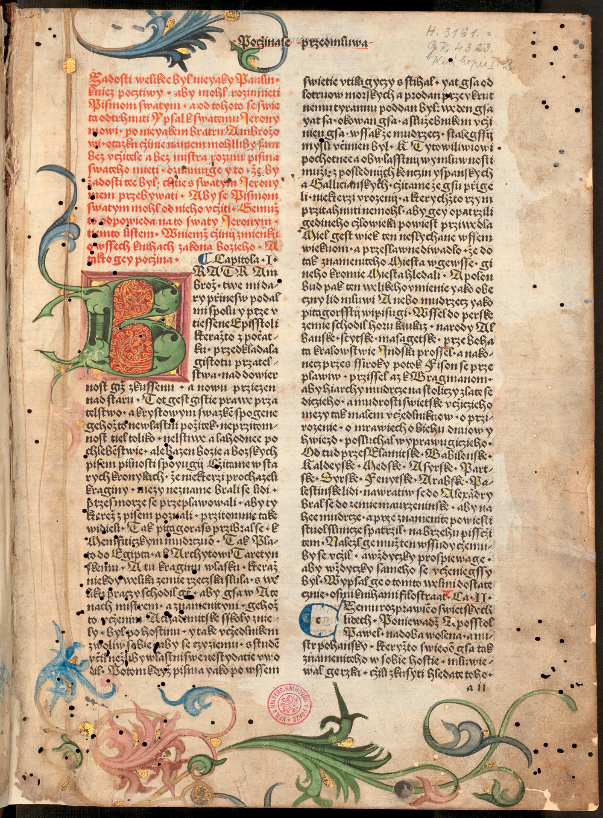

The very first edition of the Bible in Czech Republic was locally printed in the year 1488 and named the Prague Bible (see fig. 2). To put this into perspective, the first Bible printed in Germany was in 1466, closely followed by the 1471 edition printed in Italy. The Prague Bible is widely accepted as the oldest printed translation of The Vulgate into the country’s national language, Czech. Vuit argues that although this may be true, the literary and educational impact upon the Czech community abroad was limited. In contrast to other countries, the first printed Bible was a Czech translation, and no one in Prague attempted to reprint the standard Latin Bible or Latin biblical dictionaries. This is attributed to biblical authorities in Prague, the printers, and the publishers who catered to the biblical message "řečí obecnou" [in the common tongue], as established by the Husit tradition.

First page of the Prague Bible printed in 1488.

It is also probable to assume that the majority of the country’s general population did not speak or understand Latin, which further guided the development of publishing.

The greatest impact and value of the Prague Bible being the first printed book is that it could now be standardly reproduced. The book production of the year 1488 showed, for the first time, that the country’s industry is capable of greater feats, and the origins of book printing indicated more widespread means of secularising the country. Prior to the invention and acquisition of book printing, the divine law could only be distributed orally or when written by hand, reaching a smaller audience and at slower rates.

Strikingly, illustrations in Czech Bibles did not have a smooth development. Although the printer of the Prague Bible had been able to produce illustrated books prior, as evidenced in the edition of Æsop's Fables also printed in 1488, the printing of the Bible was most seriously hindered by the simplicity of its typography. Typography around the country was ineffectively individualized for each incunabula edition printed in the Czech language, and printers were only supplied with one degree in which to print all texts and headings, a limitation that even the Bible couldn’t lead to developing. The aforementioned success of stabilizing the previously handwritten biblical text, and thus reaching a wider social sphere than when the Bible was translated only by hand or orally prior, was still limited. Not making use of standardized graphic means of visualizing the text, a technique that had already been widely adopted abroad, resulted in the lack of enough graphically receptory elements in the first Czech printed Bible for any less educated reader. However, the lack of illustrations is logical in the context of the very first origins of book printing, limited by the economy and with skills only beginning to flourish.

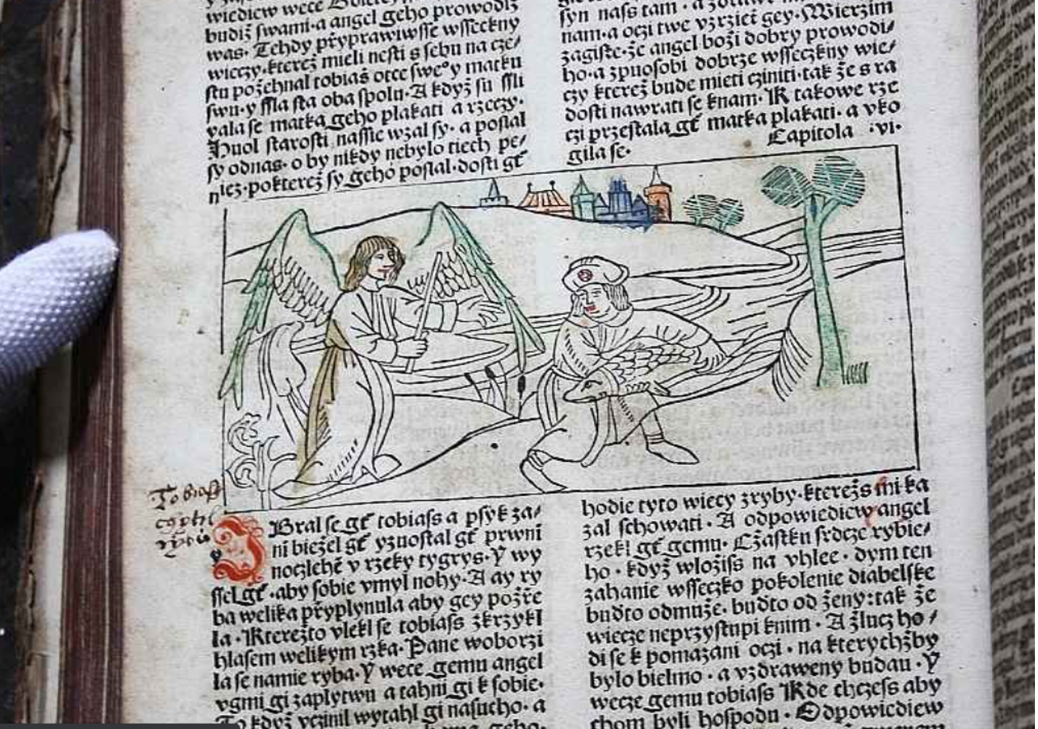

Following the Prague Bible, only a short span of time divides its publication in 1488 and the subsequent Bible Kutnohorská [Bible of Kutná Hora] in 1489. These two publications had a concurrent and competitive relationship, wherein the main element strengthening the prestige of the Bible Kutnohorská’s printer was the use of illustrations. A contemporary reader would have had no access to books other than Czech translations, where no illustrations were to be found, in contrast to foreign language books printed abroad. Thus, the Bible Kutnohorská provided such readers with an artistic transposition of the biblical plot for the first time, and was an unprecedented path towards artistic expression for many lower and middle class members of the community.

Illustration in the Bible Kutnohorská printed in 1498

It must be noted that the illustrations in Bible Kutnohorská were heavily inspired by those from the Nuremberg Chronicle of 1483, and its artistic aspirations were much lower than any imitations of Koberger’s templates for the Strasburg Bible of 1485 printed by Johann Grüninger (Vuit 480). As might be expected, the artistic standard of the Bible Kutnohorská is not comparable with that of Koberger, Grüninger, and other illustrated editions of Bibles from abroad, largely due to the artists lacking any training in the necessary skill. Eventually, artists were sent from Czech Republic to educational studios in Norimberk and Strasburg, but the second printed Bible in Czech Republic remained challenged both financially and artistically.

Before the end of the 15th century, a third edition of the Bible managed to be published, as a result of the rising demand for colored books. A group of publishers joined together towards the goal of producing another edition of the Bible, although the printing press used for Bible Kutnohorská was no longer sufficient for such a significant development. Thus, the printing was commissioned to Venice, and the third edition is accordingly named the Venetian Bible. The printer of the Prague Bible did not engage in any other complex printing after 1500, but he continued to play a role, since printing abroad would not have been possible without his matrices, which were used to cast a new typeface in Venice (Vuit 480).

The rest is history. The Bible played an unequivocal role in the foundations of the country’s book industry, and in opening everyone’s eyes to the potential that printing may hold. Although the origins of book printing in Czech Republic were limited to a few rough editions, the book industry slowly but surely continued to develop, and European countries continued influencing one another.

Source:

Voit, Petr. “České tištěné Bible 1488–1715 v kontextu domácí knižní kultury.” Česká literatura, vol. 61, no. 4, Institute of Czech Literature of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, 2013, pp. 477–501.

[Frantiska Berankova]