The mystery of the black bindings dated 1637

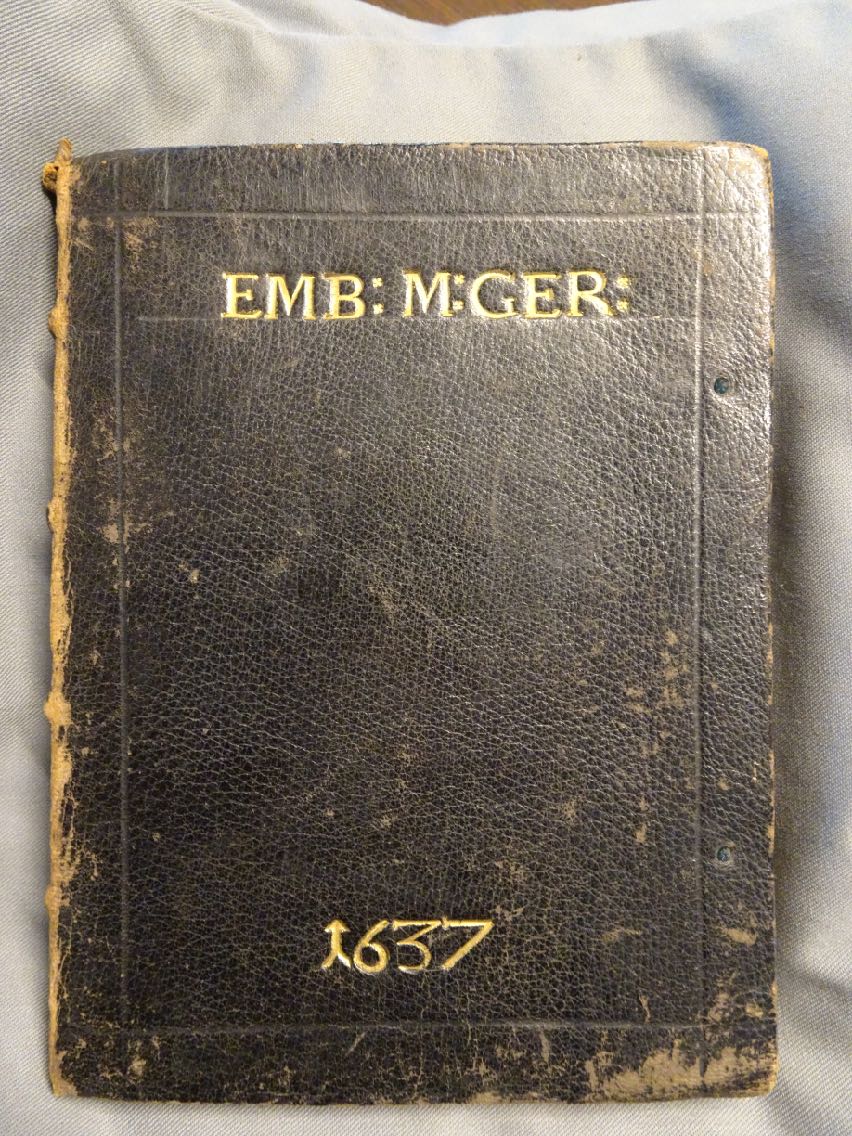

‘Het mysterie van de zwarte banden met het jaartal 1637’, the mystery of the black bindings dated 1637, this is the title of an article Herman de la Fontaine Verwey wrote in 1973 after buying Band 1 B 24 for the University of Amsterdam at the Gispen auction in May of that same year. The mystery was two-fold. The first part of the puzzle concerns the attribution of the engravings of the emblems in Apologi Creaturarum. They were long thought to have been made by Gerardus de Jode, but this was set straight in 1971 by an expert on book illustration Edward Hodnett, two years before Fontaine Verwey wrote his article. Hodnett proved the engravings were made by the Marcus Gheeraerts The Elder (c 1520-c 1590) and not by De Jode as stated by Sotheby’s in the Denison catalogue in 1933. Both men were active as engravers in Antwerp in the 16th century, but in this case De Jode was the printer. This is an important piece of information because, as Fontaine Verwey observes, whoever had this binding tooled with ‘Emb:[lemata] M:[arcus] G[h]er:[aerts]’ knew Gheeraerts was the engraver.

[***2: Iohannes Moermannus], Apologi Creaturarum. [Antwerp]: G. de Iode excu., 1584. [Colophon: Excudebat Gerardo Iudae, Christophorus Plantinus.]. In-4. OTM: Band 1 B 24.

Title and printer on the spine. At head and tail ’92’ and ‘F’, former catalogue identification of the unknown collector.

Who was this person knowledgeable of art and engravers? For whose library was this catalogue number applied. This brings us to the second part of Fontaine Verwey’s account of the mystery, and a longstanding discussion among art historians. Which collector had 1637 tooled onto the binding and why? In 1973 several notable libraries owned one or more of these black Morocco bindings, some filled with drawings, some empty. Fontaine Verwey tracked down fifteen, mainly portefolio’s for drawings and engravings made by great masters among whom Albrecht Dürer, Lucas van Leyden and Rubens. The portefolio’s must have been made for a large and priceless collection; some of the them have Dutch inscriptions, which suggests a Dutch identity for this illusive collector. Speculations have ranged from important 17th century art collectors and dealers to even Rembrandt, although the latter was soon dismissed, as there were no black bindings or portefolio’s in the sale of his collection in 1657. Later ownership marks on drawings and prints that were part of the ‘1637 collection’ before it was broken up, point to its dispersal having taken place around 1650-70’s in England and in The Netherlands.

The supposed size and value of the collection and the estimated timing of the dispersal led Fontaine Verwey to follow an earlier theory by English art historians that proposes Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel (1585-1646) as a possible contender. His wealth, his passion for all forms of art, and even the estimated period of dissipation, all fit the profile and make him a good candidate as owner of the collection. Besides, Arundel had two Dutch employés working for him, Franciscus Junius as librarian and Henrick van der Borcht Jr. for the art collection. This could explain the Dutch inscriptions on the covers. Fontaine Verwey suggests that, in view of the somewhat lesser quality of the morocco and the, for the time, rather old-fashioned lettering on the covers, the black 1637 bindings were English-made and that Van der Borcht may have had them made for the Arundel drawing and print collection to mark the beginning of his curatorship which was in 1637, hence the date on the binding. Arundel left England at the beginning of the English Civil War in 1642, to escape the political and religious unrest. Van der Borcht followed him in exile, but more was sold than bought by Arundel at that time, which, if Arundel was indeed the unknown collector behind the 1637 bindings, could explain why there are no black bindings with a later date as there were no new acquisitions to store. Arundel died in Padua in 1646, his widow lived on in Alkmaar and Amersfoort. Surviving items from Arundal’s collection were auctioned in Utrecht and Amsterdam in 1657 and 1662. Unfortuantely there is no complete inventory of Arundel’s art collection. During his lifetime and after his death, his possessions were sold in bits and pieces, not in one big sale with impressive catalogue as often was the case. Although Fontaine Verwey emphasizes he does not have hard evidence for the presumed Arundel provenance, it seems until now no one has refuted this theory.

P.L in the margins of the title-page and the engravings.

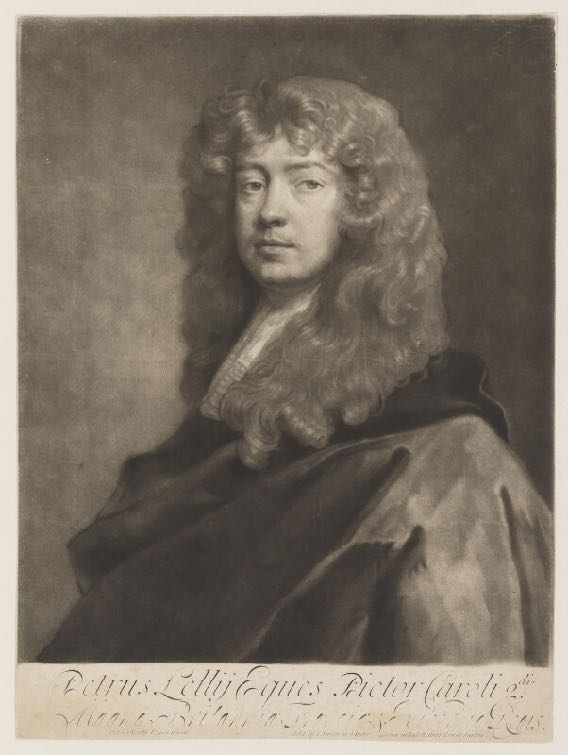

We turn our attention to what is undeniably in evidence, namely ‘P.L’ on the title-page and in the margins of all engravings. These are the initials of Sir Peter Lely (1618-1680), a naturalized British citizen of Dutch descent and much sought after portrait painter. He painted Charles I, was Principal Painter to Charles II, and was favoured by all noblemen seeking to have themselves and their dear ones portrayed. His oeuvre is impressive, probably thousands of portraits, although not all up to standard as he had the help of assistants and some were even finished after his death. He painted the Cromwells, ladies at the Royal Court, admirals and captains, and he collected. Like that of Arundel, Lely’s art collection was legendary. Pictures, drawings, prints, statues, all made by famous, mostly Dutch, Flemish and north Italian artists, Van Dyck, Rubens, Veronese and Raphael to name just a few. He was also interested in the reproduction of portraits made by and of himself, to broaden his market, the British mezzotint tradition is in part due to him.

Sir Peter Lely. 1684-88. Mezzotint by Isaac Beckett. Published by John Smith, after Sir Peter Lely. National Portrait Gallery, London.

Fontaine Verwey notes that Lely bought substantially at the Arundel sales, implying that he could have bought Band 1 B 24 there. This would prove the supposed Arundel provenance, but unfortunately, as noted above, there are no lists to confirm this, besides, there may be other possible sources for Band 1 B 24, other auctions, and Lely also bought from dealers (Dehtloff 1996, p. 25). Peter Lely died in 1680 while at work at his easel. One of his executors, Roger North, took it upon himself to organize the enormous collection of drawings and prints.

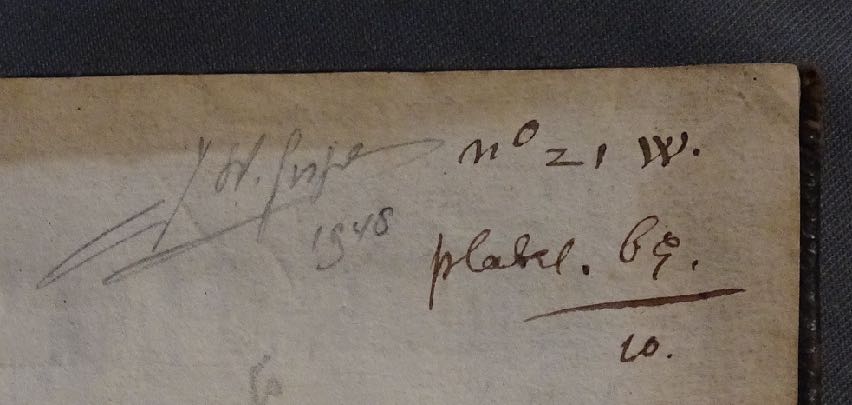

'I got a stamp, P. L., and with a little printing ink, I stamped every individual paper, and not only that, but having digested them into books and parcels, such as we called portfolios, and marked the portfolios alphabetically AA, AB, &c, then Aa, Ab, &c, then Ca, Cb, Cc, &c., so consuming four alphabets, I marked on every cartoon and drawing the letter of the book, and number of the paper in that book, so that if they had been all shuffled together, I could have seperated them again into perfect order as at first : and then I made lists of each book, and described every print and drawing, with its mark and number, the particulars of all which were near ten thousand.' Roger North, 'Notes of Me’.

Recto first flyleaf: numbering in brown ink by Roger North.

The prints and drawings were marked ‘P.L’, as was Band 1 B 24, which also has North’s numbering system in brown ink in the top right corner on the recto of the flyleaf ‘No. 21 W’ (see Dethloff 1996. Appendix II, p. 40). The first sale of drawings and prints in books and portefolio’s, in total around 10.000 items, took place in 1688 attracting not only English buyers, but also from the Continent. Lists had been made, which must have been a herculean task, but they unfortunately did not survive. Due to the superabundance and resulting lethargy at a certain point during the auction, the sale was halted halfway. The second sale of the drawings, prints and books was in 1693, and lasted six days. Band 1 B 24 was sold at one of these sales as one of the ‘unspecified numbers of bound and loose-leaved books of prints’ (Dehtloff 1996, p. 21).

Some later owners

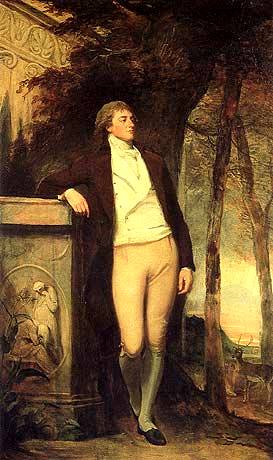

William Beckford. 1782. Oil painting by George Romney. Upton House.

William Thomas Beckford (1760-1844) was more interested in the artistic beauty of rare books and manuscripts than in aquiring series of Aldine and Elzevir imprints like some of his contemporaries. He collected special bindings, works with unusual illustrations and with interesting provenance. This set him apart, ’The result of these bizarre tastes was less a library, in the proper sense of the word, than a cabinet of bibliographical rarities and freaks, each one a gem of its kind’ (Ricci 1960, p. 85). After his death the Beckford collection went to Hamilton Palace, his daughter Susanna Euphemia having married Alexander, 10th Duke of Hamilton. Hamilton himself also had an impressive library, the two collections were not merged. The Beckford and Hamilton Libraries were sold seperately at different sales at Sotheby, respectively in 1882/3 and in 1884. Band 1 B 24 was part of the second portion of the Beckford sales at Sotheby’s. The catalogue description mistakenly identifies the emblems as ‘numerous engravings by Gerard de Jode’.

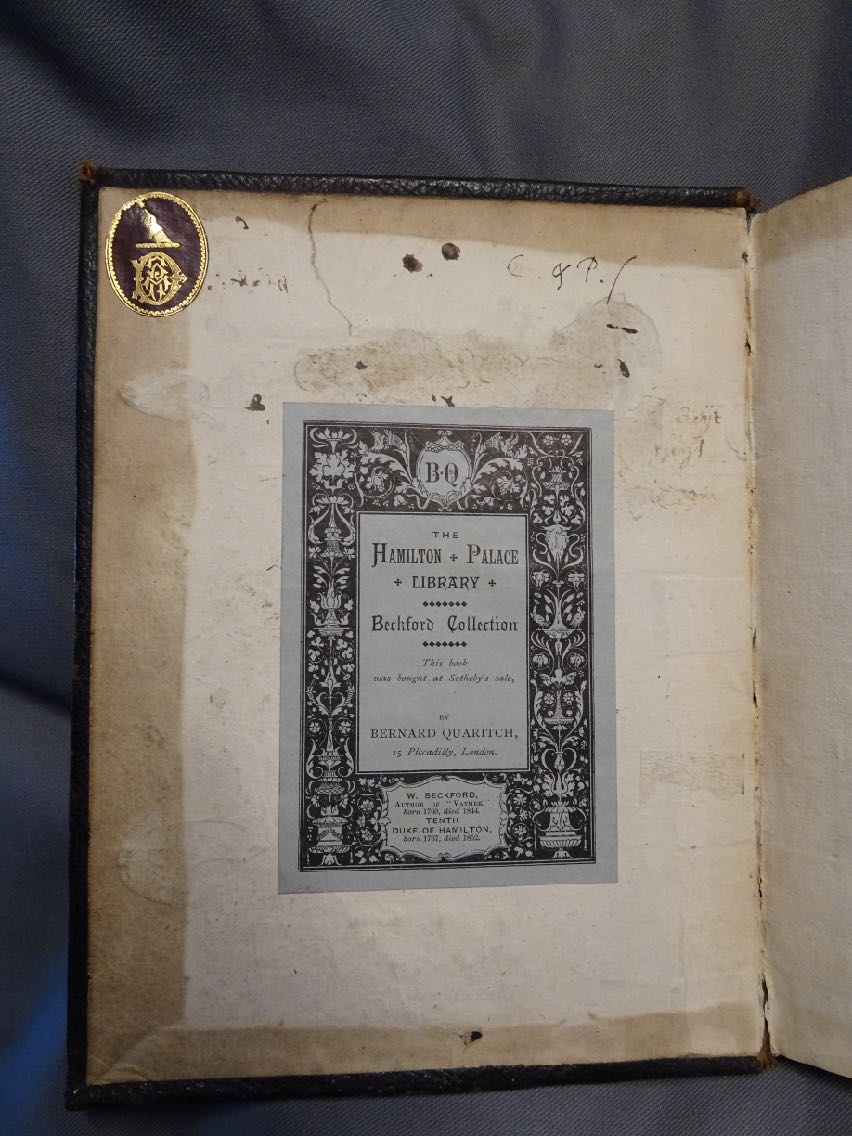

Antiquarian bookseller Bernard Quaritch had an ex libris specially made for the books he bought at the Beckford sales. Quaritch bought a large part of the catalogue.

Left pastedown: dark red morocco, oval bookplate with a pointing arm/hand above a monogram ‘ARD’.

Alfred Robert Denison, collector of angling books. Denison was originally named Robert Alfred, but reversed the order of forenames he used. He died in 1887, and specified that his books were to be kept together in trust, they were sold by auction at Sotheby’s in 1933. Here Sotheby’s omits naming the engraver at all in the catalogue description, giving just the number of illustrations.

J.H. Gispen, another collector of the old and rare. His books were sold at J.L. Beijers book auction in Utrecht in 1973, which is where Fontaine Verwey bought Band 1 B 24 with a donation from the Vereniging der Vrienden van de Universiteits-Bibliotheek. The Gispen catalogue description confirms the renewed attribution by Edward Hofnett of the engravings to Marcus Gheeraerts. No mention of Gispen in Piet Buijnsters, Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse bibliofilie, no trace whatsoever, sometimes that is how it goes.

Bought with a donation by the Vrienden van de Universiteits-Bibliotheek van Amsterdam.

It would be interesting to revisit the 1637 provenance

To dig in deeper, locate the bindings and portefolio’s Fontaine Verwey found, hope for more, and see where this gets us almost fifty years after his 1973 article.

Provenance

Possibly Thomas Howard, 14th Earl of Arundel (1585-1646)

‘1637’

Collection dispersed in auctions in Engeland and the Netherlands c 1650-70

P.L = Sir Peter Lely (1618-1680). Portrait painter of Dutch descent

Peter Lely collection of prints and drawings sold in 1688 and 1693

William Thomas Beckford (1760-1844). Novelist, art collector, polititian

Alexander Hamilton, 10th Duke of Hamilton (1767-1852)

The Hamilton Palace Library

William Hamilton, 12th Duke of Hamilton. Financial difficulties due to gambling problems

Sotheby's Hamilton Palace Libraries/Beckford sale 1882

Bought by Bernard Quaritch antiquarian bookseller

ARD = Alfred Robert Denison (1816-1887)

Denison sale Sotheby & Co. London, 1933

Bought by J.H. Gispen in 1948 (Fontaine Verwey 1973, p. 12)

J.H. Gispen (1905-1968)

University of Amsterdam. Bought at the Gispen sale, Veilinghuis J.L. Beijers, Utrecht. 29-5-1973 for Hfl. 5.000,--

Related bindings

Black bindings with 1637 (According to Fontaine Verwey 1973, p. 11)

The British Museum has four, portefolio’s with drawings by a.o. Lucas van Leyden and Albrecht Dürer.

The Rijks Prentenkabinet in Amsterdam has five, portefolio’s with engravings a.o. by Thomas Stimmer and Aldegrever.

The Lugt Collection in Paris has two, portefolio’s with drawings by Rubens a.o.

And four Fontaine Verwey does not identify, one of them presumbably Band 1 B 24, and three others.

Sales and catalogues

The Hamilton Palace Libraries. Catalogue of the Second Portion of the Beckford Library, Removed from Hamilton Palace. London: Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge, Wellington Street, Strand, 1882. [Twelfth Day. Dec. 23rd.] No. 2521. Bought by Quaritch for £9 10s.

Catalogue of the Celebrated Collection of Books Relating to Angling and of a Small General Library Formed by the Late Alfred Denison, Esq. London: Sotheby & Co., 1933. No. 158.

The Fine Library of the late J.H. Gispen esq. Book Auction Sale 29th May 1973. J.L. Beijers, Utrecht. No. 185. Estimated price Hfl. 3.000-3.500. Bought for Hfl. 5.000,- plus 16% buyer’s fee.

Bibliography

OTM: Band 1 B 24 at the University of Amsterdam

Band 1 B 24 at bandenkast.blogspot.com

The art world in Britain 1660-1735. Peter Lely. Retrieved: 30 June 2021.

Diana Dethloff, ‘The executors’ account book and the dispersal of Sir Peter Lely’s collection.’ In: Journal of the History of Collections. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996. 8 no. 1, p. 15-51.

Herman de la Fontaine Verwey, ‘Het mysterie van de zwarte banden met het jaartal 1637.’ In: Bibliotheekinformatie. Mededelingblad voor de wetenschappelijke bibliotheken. Nummer 11. December 1973.

Peter Lely. In: Frits Lugt, Les Marques de Collections de Dessins & d'Estampes. L.2092. Retrieved: June 2021.

Peter Lely. Portrait. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

‘Sir Peter Lely’s Collection.’ Editorial in: The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. Illustrated Published Monthly. London: The Burlington Magazine, Ltd. No. 485. Vol. lxxxiii, August 1943. p. 185-188.

Christopher Maxwell, The Dispersal of the Hamilton Palace Collection. PhD Thesis, University of Glasgow. 2014. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/5197/ ‘Due to copyright reasons unavailable for viewing.’

Roger North, Notes of Me. Edited by Augustus Jessop and published as The Autobiography of The Hon. Roger North. (London: 1887). ’The art world in Britain 1660 to 1735,' at https://artworld.york.ac.uk/sources/5.1633.0010. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

Seymour de Ricci, English Collectors of Books & Manuscripts (1530-1930) and their Marks of Ownership. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1960 [1930]. p. 84-87.

[Pam van Holthe]