The acorn, essential for many

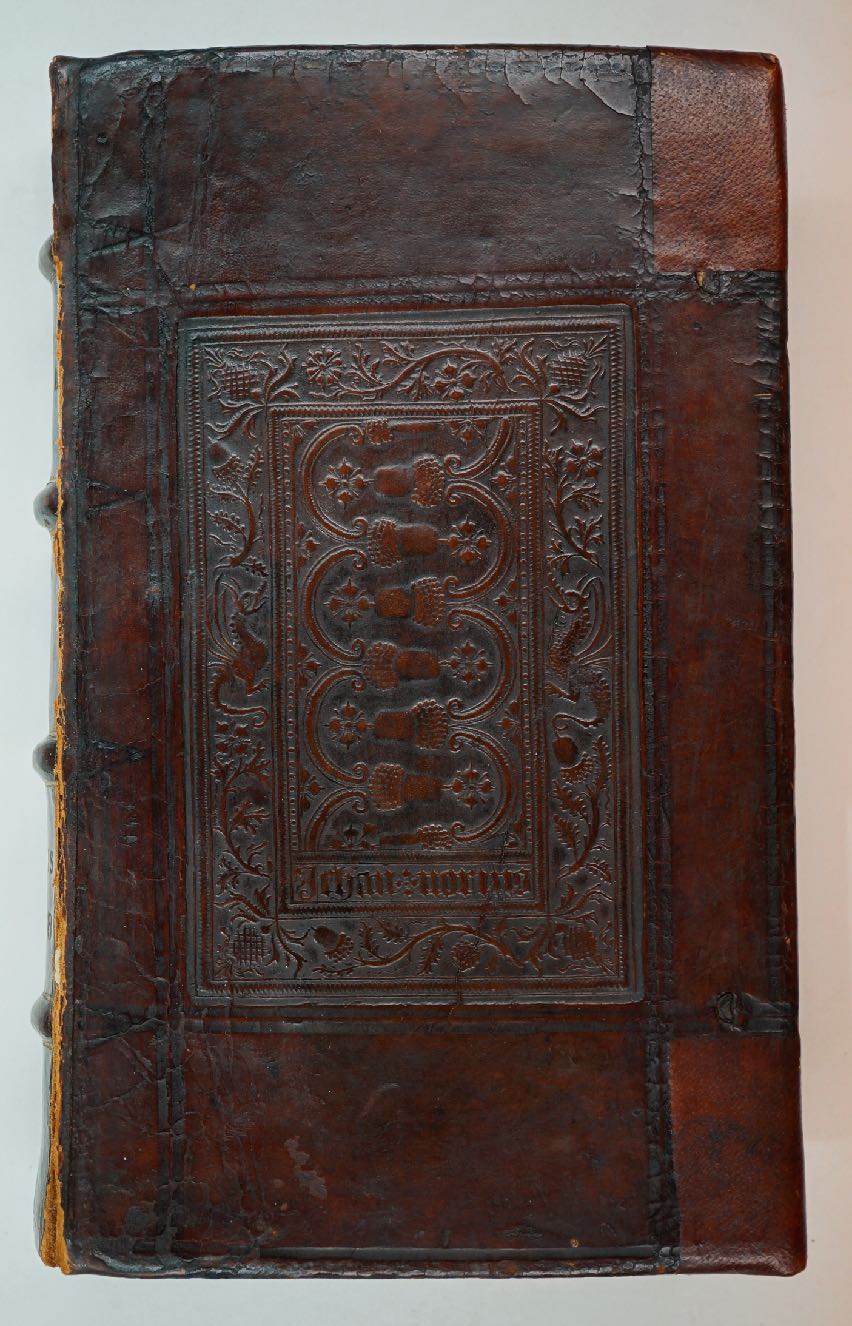

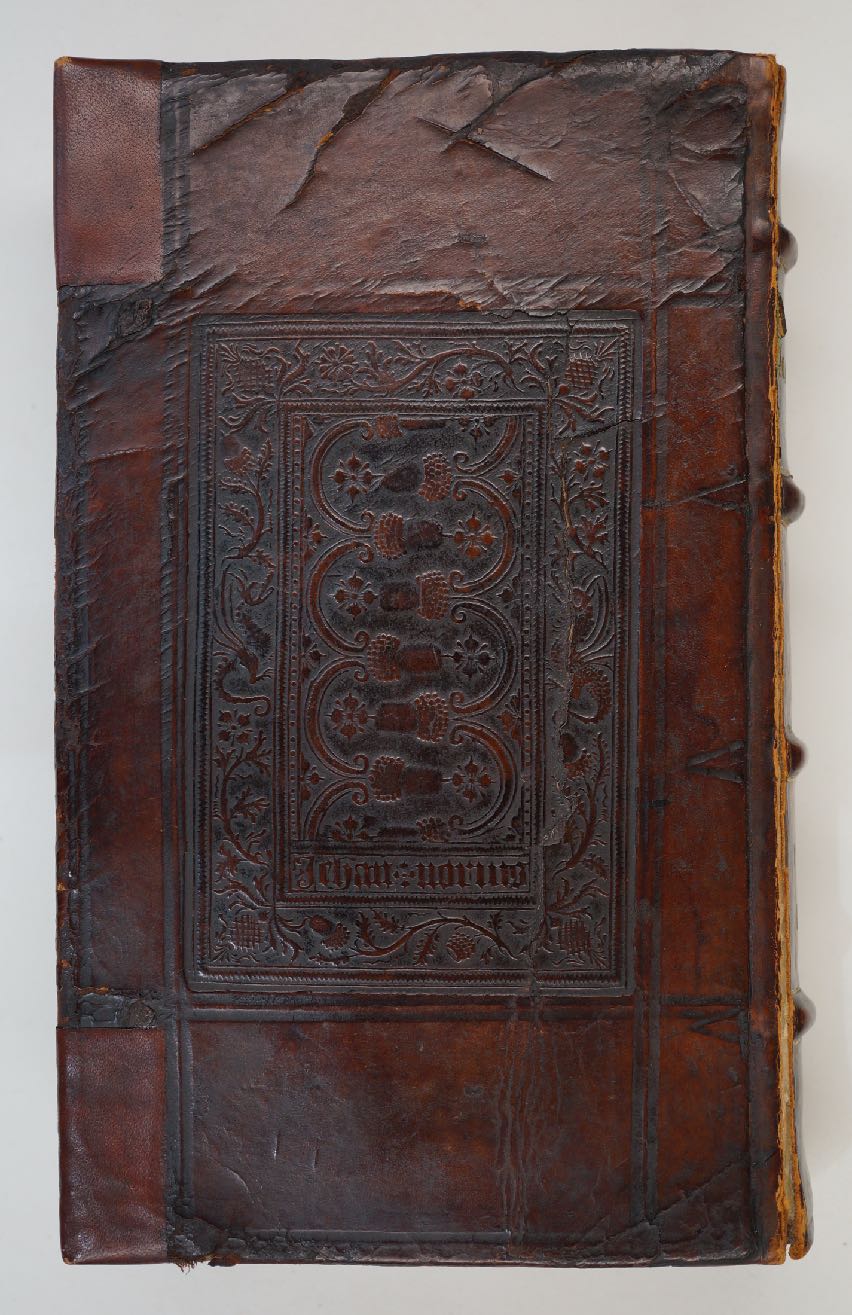

Martialis, Epigrammaton Libri XIIII. Parisiis: Apud Simonem Colineum, 1528. In-8. OTM: Band 1 H 16

Good health, wisdom, luck, abundance, eternal youth, potential, perseverance and longevity. All these characteristics and more have been attributed to the oak tree, and as a consequence also to the acorn. Early adopters were the pre-Christian Druids, which translated meant oak-knowers. The mighty oak gives its strength to its seeds the acorns, which in turn, when eaten, provide a wide range of animals such as deer, chipmunks, rabbits, pigs, goats, buffaloes, mice, voles, possums, blue jays, badgers, squirrels, pigs, boars and moose with minerals, calcium and vitamins to supplement their herbivorous diet. Together with beechnuts they are also an essential staple for them to survive the winter. When acorns are in short supply as is forecast for the coming winter, if there are not enough to go around, the more vulnerable animals will starve. As for human edibility, acorns are edible but are a pain to prepare as they need lengthy leaching to remove tannins that are poisonous if consumed in large quantities. Having said that, acorns were used in traditional American Indian cookery, apparently still are, and it will not surprise that acorns also form part of the currently fashionable vegan and vegetarian diet. The acorn was also a motif in Greek and Roman art and architecture, in Northern Europe it was applied as ornament on cutlery, furniture, jewellery and playing cards, and it still is a present-day spiritual symbol.

All of this a digression from the main subject of this post, Band 1 H 16, to show that the acorn on this bookbinding was not a randomly picked decoration, but a long established, universal symbol of growth, life and immortality, in heraldry of independence, all of which can be seen as distinctive qualities, although the value of immortality is debatable.

In the first half of the sixteenth century, the acorn panel was a favoured choice for books bound for the traditional customer (Fogelmark 1990 p. 158). Unlike the panels with Lucretia (rape and suicide) Cleopatra (lust and murder), no offence could be taken at the acorn’s connotation of peaceful pro-life. As a result a sizeable amount of bookbindings with acorn panels have survived, it is one of the most common sixteenth century panel stamps. Variations have been found though on bindings made in different countries, which caused some discussion about the origins of the acorn panel within the circle of early twentieth century pioneers of bookbinding research such as G.D. Hobson, M.J. Husung, L. Verheyden, E.PH. Goldschmidt and L. Gruel. The latter suggested that the panels originated in France, however this was considered by Husung a patriotic supposition for which there was no decisive proof (Husung 1918-19 p. 185). At the end of the century Gid & Lafitte 1997 lists even more variants, all on French bindings, dated by them from ca. 1494 onward which could substantiate Gruel’s belief in its French origin. Nevertheless, at the moment it is generally assumed that the acorn panel originated in Louvain and was subsequently also used by binders in the rest of Flanders, England, France and Italy (Fogelmark p. 142-43.), the French items are identified as ‘de type flamand’ by Gid & Lafitte.

The shield tells all, or nothing

Most acorn panels have blank shields, like many panels on 16th century bookbindings they are usually unsigned. Although the shield on Band 1 H 16 exceptionally does have a name in the shield, that of Jean Norins, it is thought that panels with his name were not actually made by Norins, but by an an anonymous craftsman. With the introduction of the panel stamp in the first half of the sixteenth century, several copies of the same panel could be cast from the same mould, to be distributed to numerous bookbinders, who could put their own name on the blank shield, as did Norins. (Fogelmark 1990 p. 140). More often than not the shield was left blank.

Finally

The ins and outs of the making of the panel stamp are for another time.

Provenance

Quite a few former owners

Binder: Jean Norins. Presumed to be Jehan Norins/Norvins/Norius/Noruis ‘der ältere’ active ca. 1523-1545 in Paris and Louvain. A bookbinder, possibly also bookseller, Norins moved to Louvain in the 1530’s.

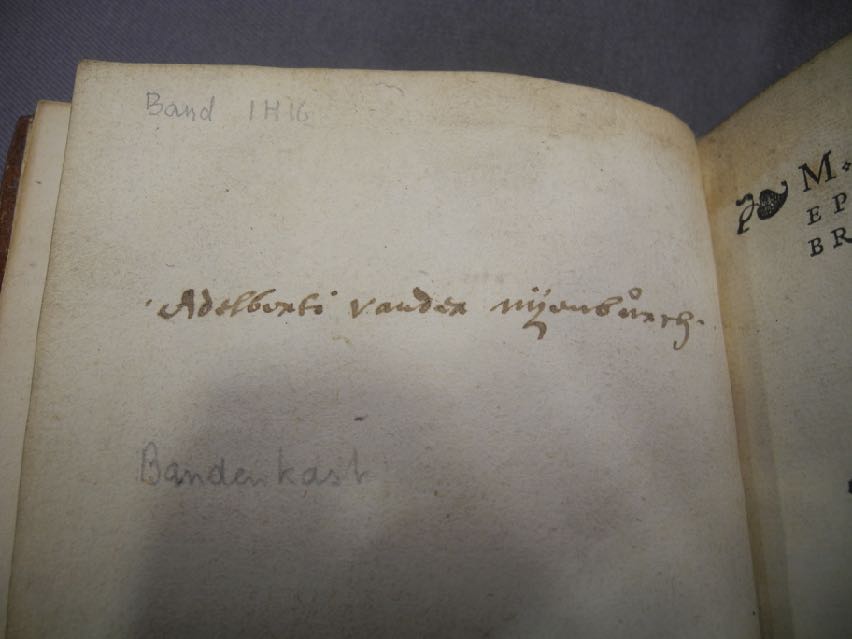

Adelbert van Egmond van der Nijenburch (1534-1609) Secular clergy. Canon of the Oud Munster church in Utrecht.

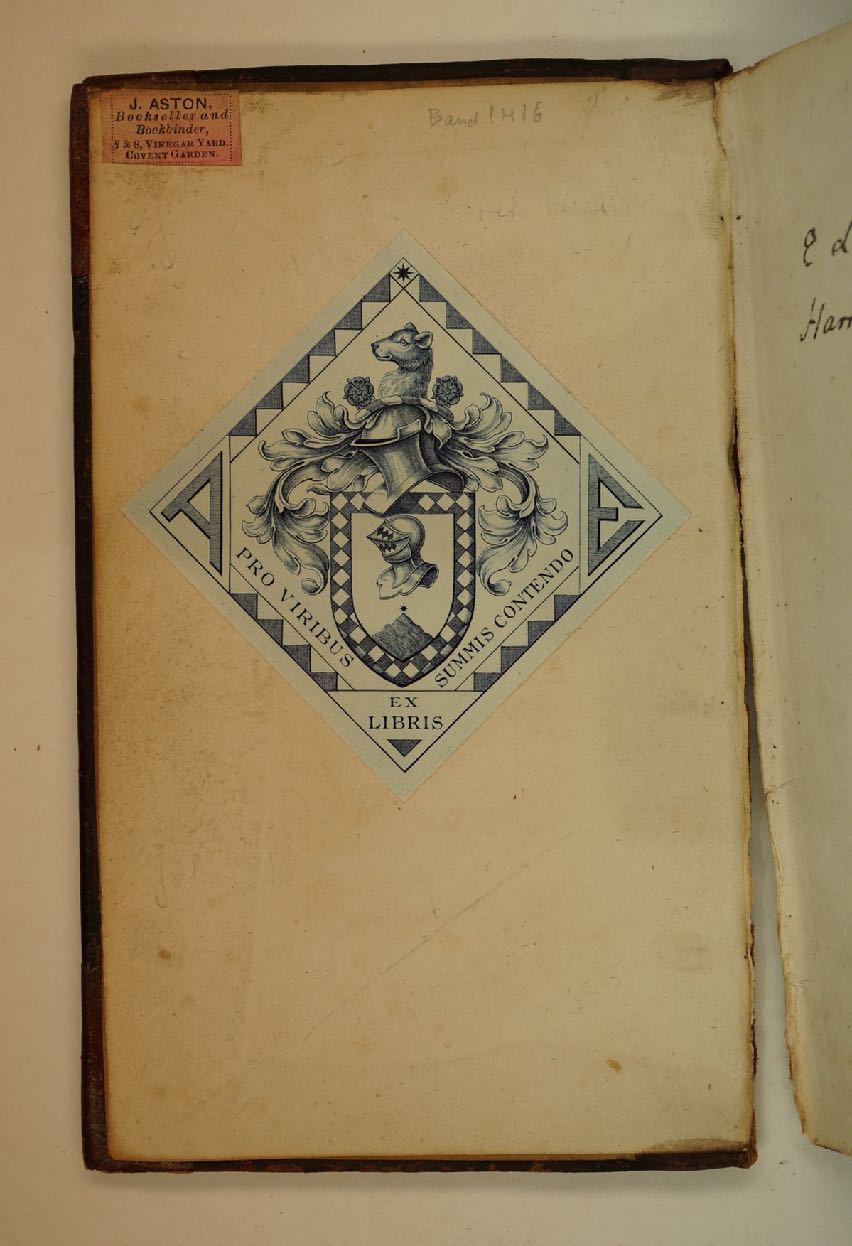

J. Aston, London. Bookseller and bookbinder, 7 & 8 Vinegar Yard, Covent Garden, London. Active before 1890. Declared bankrupt by the High Court of Justice in Bankruptcy, 21th July 1890. The London Gazette, July 25, 1890.

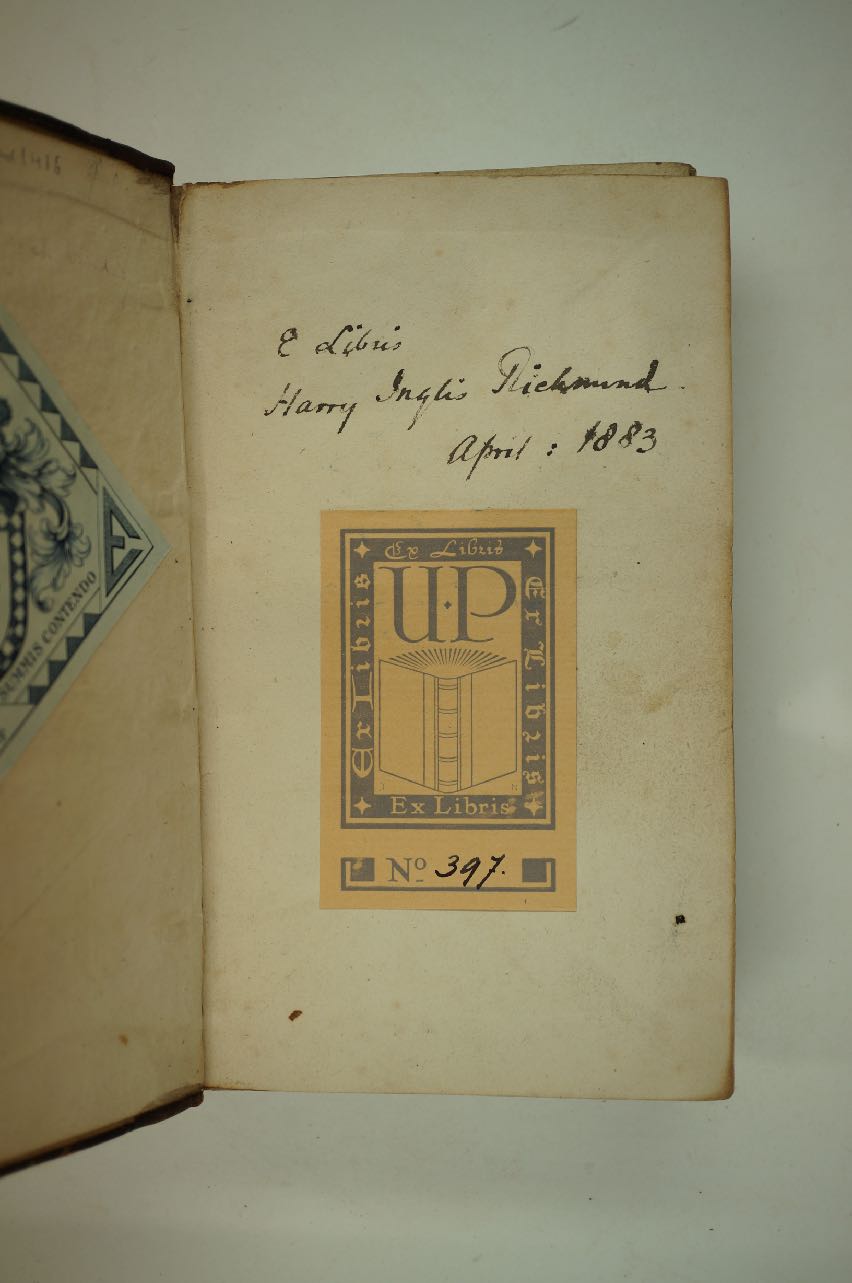

Harry Inglis Richmond (1849-1920) Bought Band 1 H 16 in April 1883, from J. Aston? ‘He was a brilliant scholar, and great things had been expected of him both at Charterhouse and Oxford, but somehow he had never done them, and had settled down into a pleasant good-natured gossip and connoisseur, with a wonderful talent for mimicry. Inglis would give an imitation, for instance, of an old verger showing tourists round a French cathedral which was so lifelike as to have a touch of genius, and that was only one item in his repertoire. This and other social qualities made him much in request, and he probably found his life agreeable enough as a rule, though I think there were times when he felt that it was rather a wasted one. I can see him now, a stout short figure, with a twinkle behind his single eye-glass, and a look of an omniscient jackdaw on his round face. Thomas Anstey Guthrie, "A Long Retrospect", 1936.

‘AE’ is Albert Ehrman (1890-1969). Ehrman gave the British Museum a book a year on the occasion of his birthday! A publication of the highlights of his rare bookbindings collection was made by Howard Nixon in 1956: The Broxbourne Library. Styles and Designs of Bookbindings from the Twelfth to the Twentieth Century. Band 1 H 16 was not part of the Ehrman sales.

Proost probably bought Band 1 H 16 from Ehrman, either directly or through an antiquarian bookseller.

UP is Ulco Proost (1885-1966). As a collector Proost maintained a low profile, acording to Buynsters 2010 this was in part to avoid spying by the tax collector. The sale of his books at Beijers auction in Utrecht was anonymous, at which sale the University of Amsterdam bought quite a few lots.

University of Amsterdam. Bought at Veilinghuis J.L. Beijers, Utrecht. 7/8-11-1967 for Hfl. 550,-- plus 16% buyer's premium

Sales and catalogues

The Fine Library of a Well-Known Amsterdam Collector [Ulco Proost]. Book Auction Sale November 7 and 8, 1967. Utrecht: J.L. Beijers, 1967. No. 1605. Estim.price: Hfl. 250-300. Sold for Hfl. 550, plus 16% buyer's premium.

Sotheby's 1977 and 1978 Ehrman sales catalogues. Band 1 H 16 was not part of these sales.

Bibliography

OTM: Band 1 H 16 at the University of Amsterdam

Band 1 H 16 at bandenkast.blogspot.com

Yves Devaux, Dix siècles de reliure. Paris: Pygmalion, 1981 (1977). Drawing of the same Jean Norins acorn panel. p. 44.

Piet J. Buijnsters, Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse bibliofilie. Boek- en prentverzamelaars 1750-2010. Nijmegen: Uitgeverij Vantilt, 2010. p. 12.

Elly Cockx-Indestege, Jan Storm van Leeuwen & Dirk Imhof, Estampages et dorures. Six siècles de reliures au Musée Plantin-Moretus. Catalogue de l’exposition 15 octobre 2005 - 15 janvier 2006. Anvers: Musée Plantin-Moretus/Cabinet des Estampes, 2005. Same acorn panel, signed Jean Norins. II.2.

‘Cooking with Acorns: A Major North American Indian Food.’ Online. Retrieved 8-10-2021.

Staffan Fogelmark, Flemish and Related Panel-stamped Bindings. New York: Bibliographical Society of America, 1990. 'Blank shields' p. 126-151. Plate XLI (rubbings).

M. Foot, The Decorated Bindings in Marsh's Library, Dublin. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004. p.77-78.

M. Foot, The Henry Davis Gift. Volume III. A Catalogue of South-European Bindings. London/Delaware: The British Library/Oak Knoll Press, 2010. No. 11.

Denise Gid et Marie-Pierre Lafitte, Les reliures à plaques Françaises. Turnhout: Brepols, 1997. Bibliologia. Volume 15. Variants of acorn panels: Nos. 95-115.

E.Ph. Goldschmidt, Gothic and Renaissance Bindings. London: Ernest Benn, Ltd., 1928. Various acorn panels: 131 (acorn panel identical to that on Band 1 H 16, also signed Norins)-138; p.231 on variants of acorn panels.

Léon Gruel, Manuel historique et bibliographique de l’amateur de reliures. Paris: Gruel & Engelmann, 1887. p. 122, 137 plate 2 (Same panel as Goldschmidt 1928 No. 131).

A. Hulshof and M.J.A.M. Schretlen, De kunst der oude boekbinders: XVde en XVIde eeuwsche boekbanden in de Utrechtsche Universiteitsbibliotheek. Utrecht: Nederlandsche Vereeniging van Bibliothecarissen en Bibliotheekambtenaren, 1921. N. 15.

M.J. Husung, ‘Zur Praxis und zur Psychologie der älteren Buchbinder. Nach Einbänden in der Universitäts-Bibliothek zu Münster i. W.’. In: Zeitschrift für Bücherfreunde. Herausgegeben von Georg Witkowski. Leipzig: Verlag von E.A. Seeman. N.F. (ser. 2) zehnte Jahrgang, zweite Hälfte. 1918-19. p.181-193. a.o. on Jean Norins and the discussion on the origin of the acorn panel stamp. Online at archive.org. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

Some Jean Norvi(n)s bindings with acorn panels bandenkast.blogspot.com

Prosper Verheyden, 'Banden met blinddruk bewaard in het Museum Plantin-Moretus.' In: Tijdschrift voor Boek- en Bibliotheekwezen. Antwerpen/'s-Gravenhage: J.-E.Buschmann/Martinus Nijhoff, 1906. On the acorn panel and Jean Norins p. 122-124.

W.H.J. Weale, Bookbindings and Rubbings of Bindings in the National Art Library South Kensington. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1898. 2 vols. Vol. I, p. lxxv. ; Vol.II, No. 421.

King of Acorns. Woodcut. ca. 1540. Playing card by Peter Flötner (Thurgau 1485–1546 Nuremberg). One of 47 German-suite playing cards. Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg. GMN Sp 7418 1-47 Kapsel 516.

[Pam van Holthe]