Schwitters and Jarry at the Gaberbocchus press

Franciszka Weinles was born on 28 June 1907 in Warsaw, the daughter of the Jewish artist Jakub Weinles. She graduated from the Academy of Fine Art in Warsaw in 1931. Stefan Themerson was born on 25 January 1910 in Plock, Poland (then part of the Russian Empire). His Jewish father was a physician and social reformer. Stefan studied physics and then architecture at Warsaw University, but his real early interest was photography and film making. The two met in 1929 and were married two years later.

Franciszka Weinles was born on 28 June 1907 in Warsaw, the daughter of the Jewish artist Jakub Weinles. She graduated from the Academy of Fine Art in Warsaw in 1931. Stefan Themerson was born on 25 January 1910 in Plock, Poland (then part of the Russian Empire). His Jewish father was a physician and social reformer. Stefan studied physics and then architecture at Warsaw University, but his real early interest was photography and film making. The two met in 1929 and were married two years later.

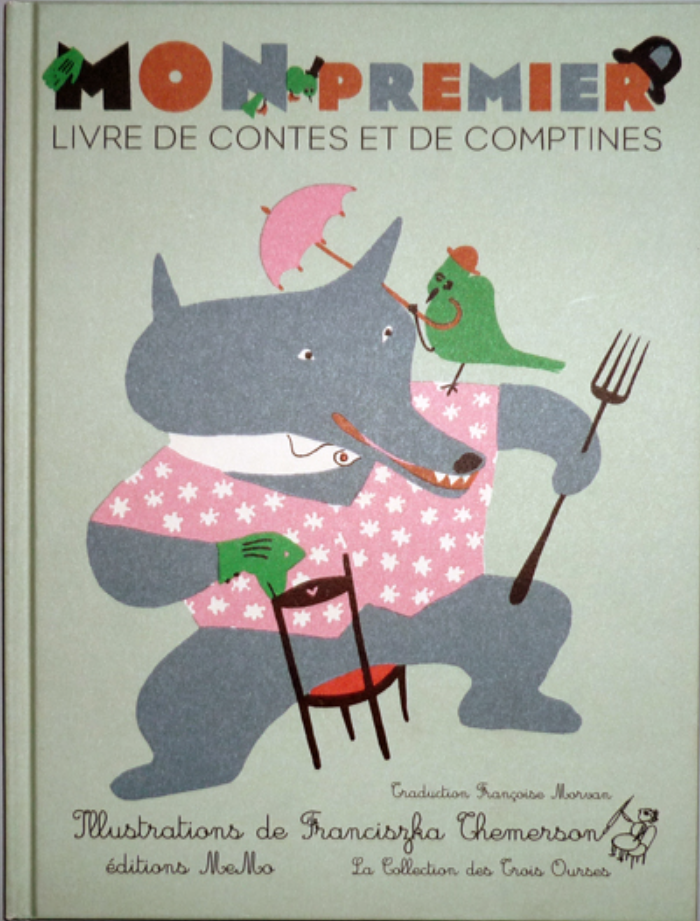

Living in Warsaw until 1935, Stefan wrote children book that were illustrated by Franciszka. Together they produced a number of short experimental films. In the winter of 1937/8 the couple moved to Paris joining an international circle of artists and writers. Stefan wrote for various Polish publications in Paris; Franciszka illustrated children’s books for Flammarion.

With the declaration of war in 1939, both enlisted. Stefan joined the Polish army; Franciszka was seconded as a cartographer to the Polish Government in Exile, first in France and from 1940 in London. With the German invasion and the Allied collapse, Stefan found himself desperately trying to escape from France. Towards the end of 1942 he succeeded to make his way to Lisbon and was transported to Britain by the RAF.

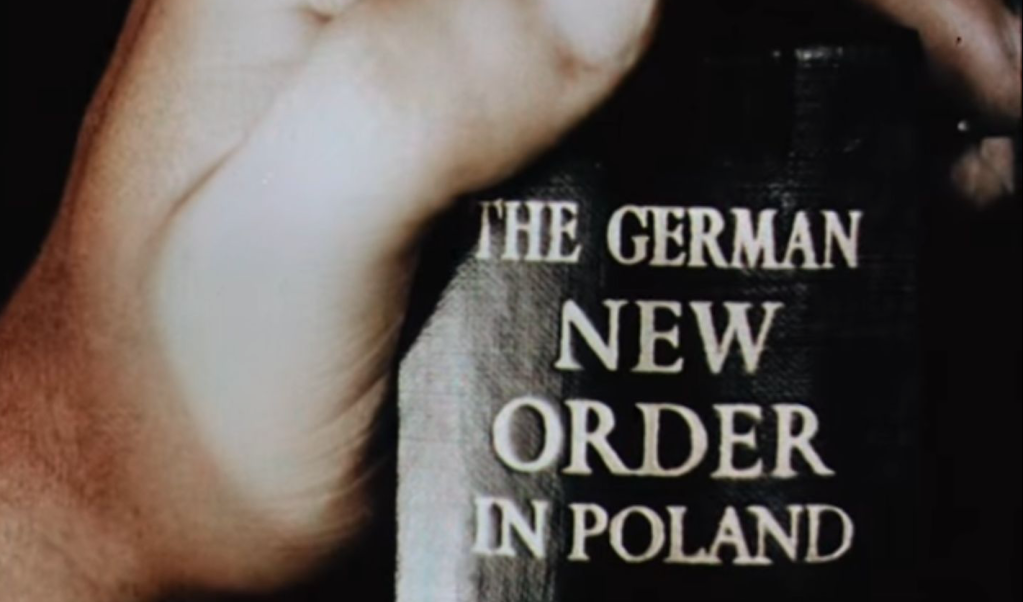

Having been reunited with his wife, he joined the film unit of the Polish Ministry of Information and Documentation. There he and Franciszka produced Calling Mr Smith, an account of Nazi atrocities in Poland. In 1944 the Themersons moved to the West London district of Maida Vale, where they would stay for the rest of their lives. At the time of their naturalisation on 13 April 1954, the couple lived at no. 49 Randolph Avenue.

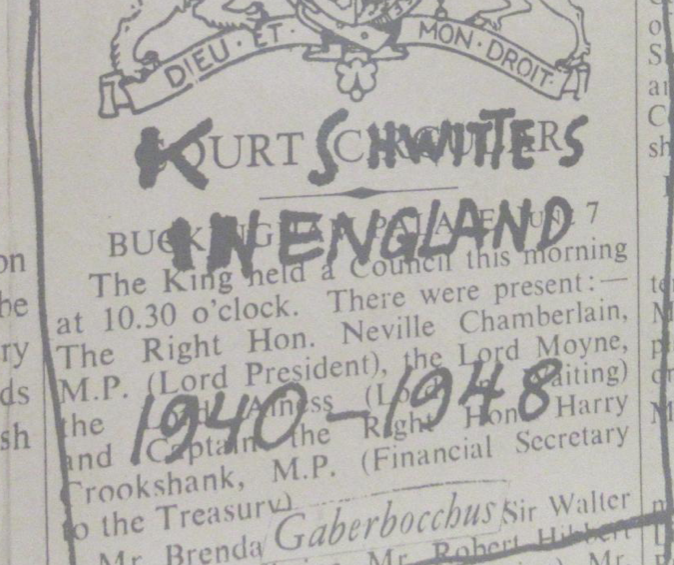

Stefan and Franciszka established the Gaberbocchus Press in 1948. The choice of name was inspired by the Latinised version of Lewis Carroll’s inventive nonsense poem ‘Jabberwocky’ that was included in his 1871 novel Through the Looking-Glass.

With Franciszka as artistic director and Stefan as editor, the Press was active until 1979 and published fifty-nine titles. In the typical private press tradition, work began from home by printing their first books on a hand-press using hand-made paper. As the press developed the titles were professionally printed. They kept an office in Formosa Street where, from 1957 to 1959, they also ran the Gaberbocchus Common Room which was a meeting place for artists, scientists, and members of the public to exchange ideas and enjoy readings, music performances, and film screenings.

A characteristic of all the Press’s publications was the intimate relationship between image and text as an expression of content. The output included works by Apollinaire, Jankel Adler, and Bertrand Russell’s The Good Citizen’s Alphabet. Gaberbocchus also introduced Kurt Schwitters to an English audience.

Born in June 1887 in Hanover and educated at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Dresden, Schwitters was conscripted into the army between March and June 1917, but was declared unfit for active service. The senseless slaughter of war had shaken his faith in the cultural norms of his generation. He became a prominent figure within the Dada movement, but his status was undermined with the rise of Hitler.

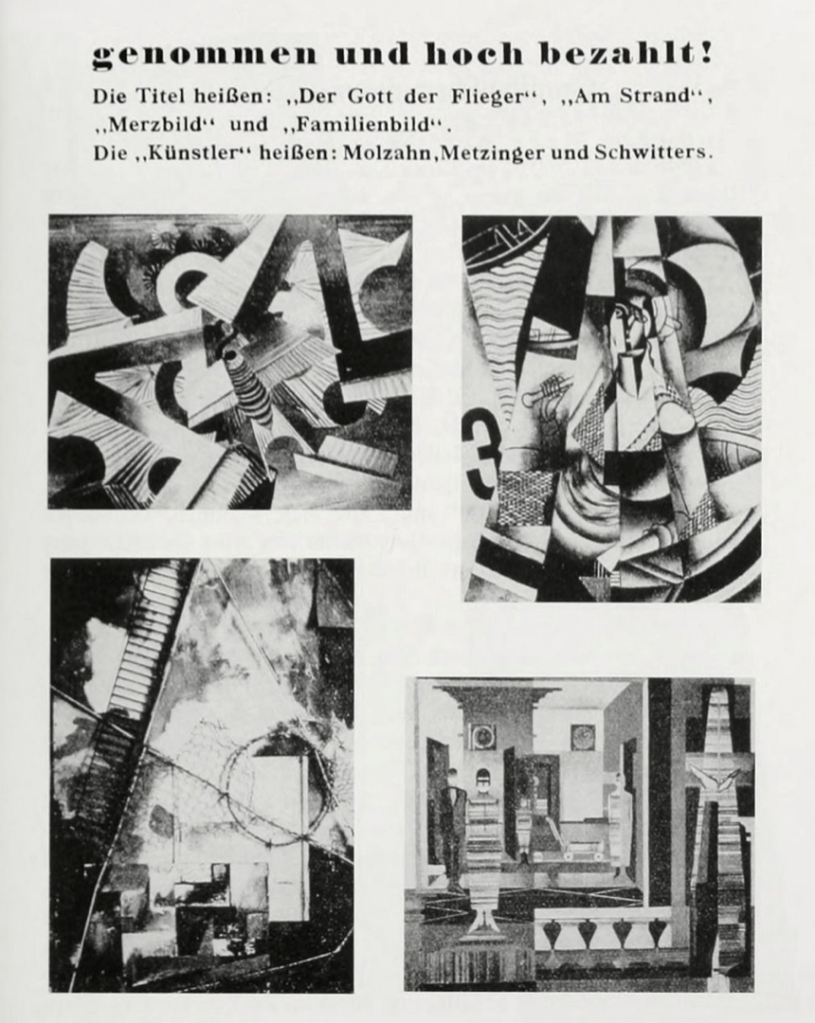

In 1937, four of his works were included in the notorious Entartete Kunst (‘Degenerate art’) exhibition. Thirteen other works were removed from German museums. Forced to leave Germany he settled at Lysaker, near Oslo. When German forces attacked Norway he fled to Britain, arriving in Edinburgh in 1940.

Kurt’s Dadaist reputation meant nothing in England. Singled out as an enemy alien, he was interned at Douglas on the Isle of Man. Behind barbed wire, Hutchinson Internment Camp held so many academics and artists that it functioned as a kind of university-in-exile. Kurt Schwitters performed his poems there and painted portraits.

After obtaining his freedom he returned to London and moved into an attic flat at no. 3 St Stephen Crescent, Paddington. He exhibited in several galleries, but with little success. At his first solo exhibition at the Modern Art Gallery in December 1944, forty works were displayed but only one was sold. An outsider, he remained virtually unknown as an artist. In 1944, he met Edith ‘Wanty’ Thomas. In 1945 they moved to Ambleside in the Lake District. On 7 January 1948 Schwitters received news that he had been granted British citizenship. He died the day after.

Themerson first met Schwitters in 1943 at a London meeting of the PEN Club. Kindred spirits, they became friends. In 1958, the Gaberbocchus Press published Schwitters in England: 1940-1948, the first presentation of the author’s prose and poems in English. In his introduction Stefan praises Kurt’s art of collage as a conscious attempt to ‘make havoc’ of cultural conventions. The presentation of the book was a fitting tribute. Its unorthodox design with multi-coloured papers and striking cover reflects a rejection of established procedures that Schwitters would have appreciated.

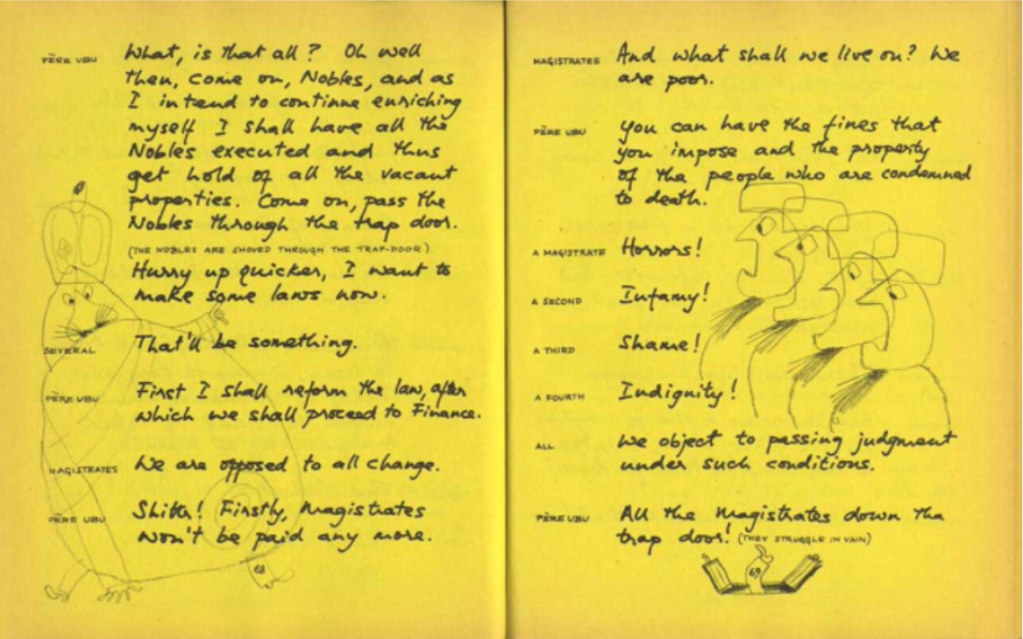

Averse of the vulgar commerciality of publishing, a key objective of the Press was to produce ‘best lookers rather than best sellers’. A refusal to conform is best illustrated by the 1951 publication of Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi.

Hallmarks of the playwright’s style are absurdity and irreverence, characteristics that inspired the Themerson edition. Printed on yellow paper, Barbara Wright produced her translation by hand on lithographic plates to which Franciszka added the witty drawings that capture the spirit of the play. For its presentation and design, it became the most acclaimed book of the Gaberbocchus Press.

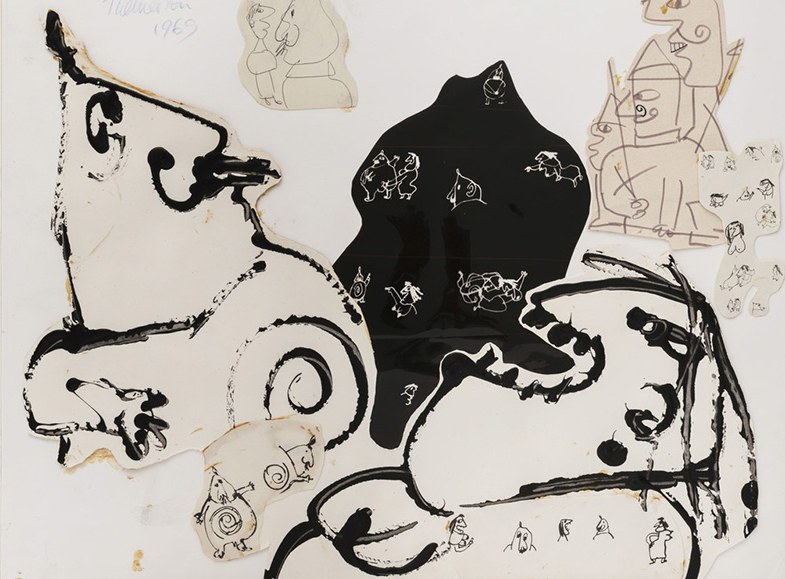

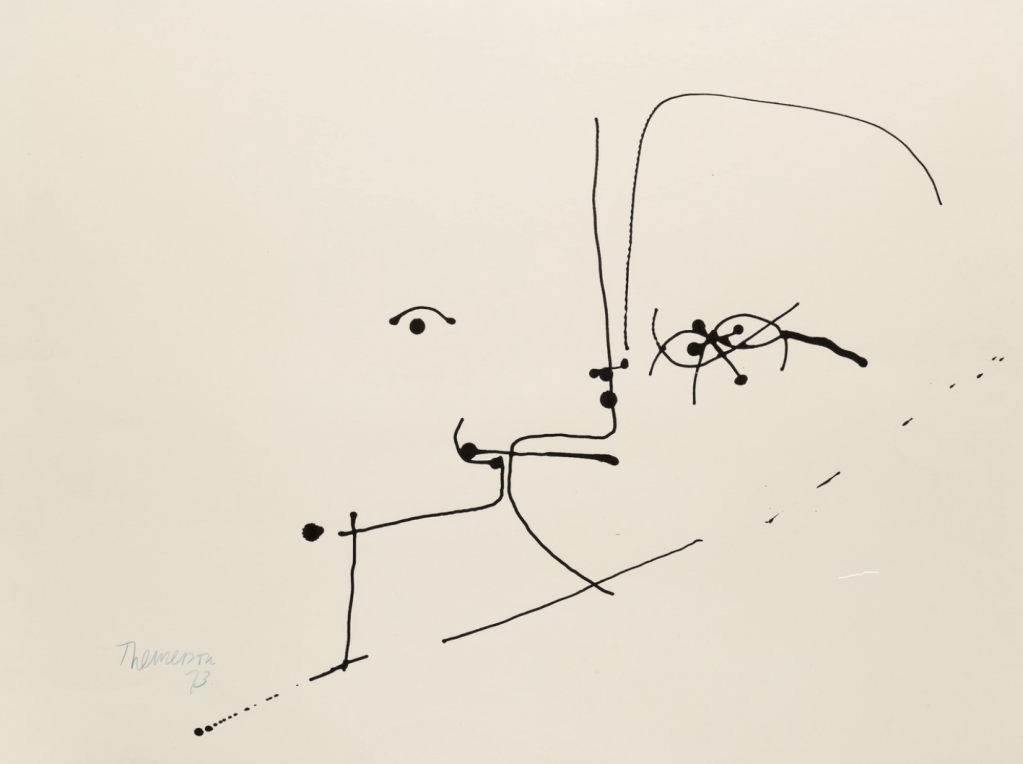

In 1952, Franciszka created masks for a reading of the play at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London; she also designed life-size puppets for s stage performance by the Stockholm’s Marionetteatern in 1964, and finally drew ninety episodes of a comic-strip version of Ubu in 1969.

At Themerson’s invitation, the Gaberbocchus Press was taken over by De Harmonie publishers in Amsterdam in 1979. Two years later, Stefan delivered the annual Huizinga Lecture at Leiden University and it was through this strong Dutch connection that some of his novels gained recognition in the English-reading world. In 1985, De Bezige Bij in Amsterdam published a translation of an English manuscript which they titled Euclides was een ezel (‘Euclid was an ass’). It motivated Faber & Faber to publish an English version in 1986, now called The Mystery of the Sardine.

Franciszka died in London in June 1988. Stefan passed away in September that same year. Together, they had spent more than four creative decades in exile, underscoring Stefan’s credo that writers carry their culture with them wherever the city of refuge may be. Having to resist threats of patriotic fervour and nationalism, exile – be it externally or self-imposed – is the artist’s natural condition.

[Jaap Harskamp]