Penninck-boeck time warp

A numismatic work, printed in 1597, first bound sometime between 1751 and 1769 almost two centuries later. It was found between a pile of waste papeer. Had it been a living being, the work in this binding would have experienced a traumatic, cultural shock. As it is, it was saved from possible destruction by a very pleased Penninck-Boeck-lover.

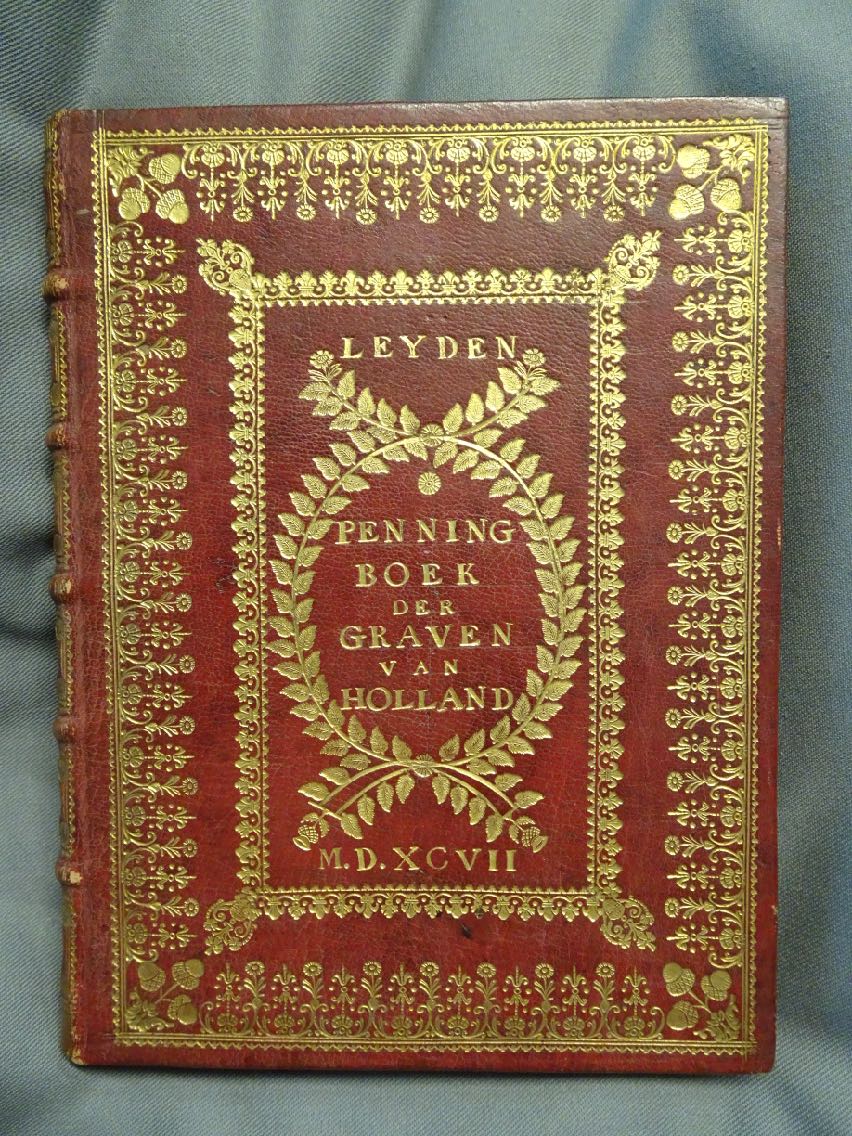

[Erasmus van Houwelingen], Penninck-boeck inhoudende alle Figuren van Silvere ende Goude penningen geslaegen byde Graeven van Hollandt. Tot Leyden: By Francoys van Ravelenghien, 1597. In-4. OTM: Band 1 B 7.

Who was the lucky finder of the bundle of uncut, unbound leaves of the Penninck-Boeck? The happy man was Jacob Kortebrant, important enough to merit an entry in the Nieuw nederlandsch biografisch woordenboek in 1914. Kortebrant worked as a pawnbroker for the ‘Bank van Lening’ all his life, but also derived great pleasure from his activities as historian, artist and poet. The former two with more success than the latter. A book on Rotterdam was published posthumously in two editions, his drawings were catalogued and were still to be found in the Rotterdam archive in 1914. Even though his poetry was not considered to be of great lyrical quality, he was asked to write occasional poetry for a festivity now and then. Unfortunately for Kortebrant his eyesight deteriorated at the end of his life, eventually causing blindness, but fortunately this must have been after he found what he had been endlessly looking for, the Penninck-Boeck. After his death his earthly possessions were sold, the prints and books for the sum of fl. 2112. Was Band 1 B 7 part of this sale?

But let us go back to its conception. According to the six-page manuscript ode, indeed a poem, on the first blank pages of the Penninck-Boeck, written in 1769 on his 72nd birthday, Kortebrant had been obsessively looking for the Penninck-Boeck for years. He finally found an unbound copy between an assortment of used and discarded paper.

‘Eindelijk kogt ik den

eersten druk onder eenige scheurpapieren

die met de schrijfpenne bebroddelt en

bemorst waren, en dat in losse bladen;’

Miraculously the book was complete. Kortebrant personally washed the sheets to perfection, as was the going trend in the second half of the 18th century.

‘Toen liet ik, door een nette hand,

Dit binden in dees rooden band

van Marokkijnenleer en vergulden…’

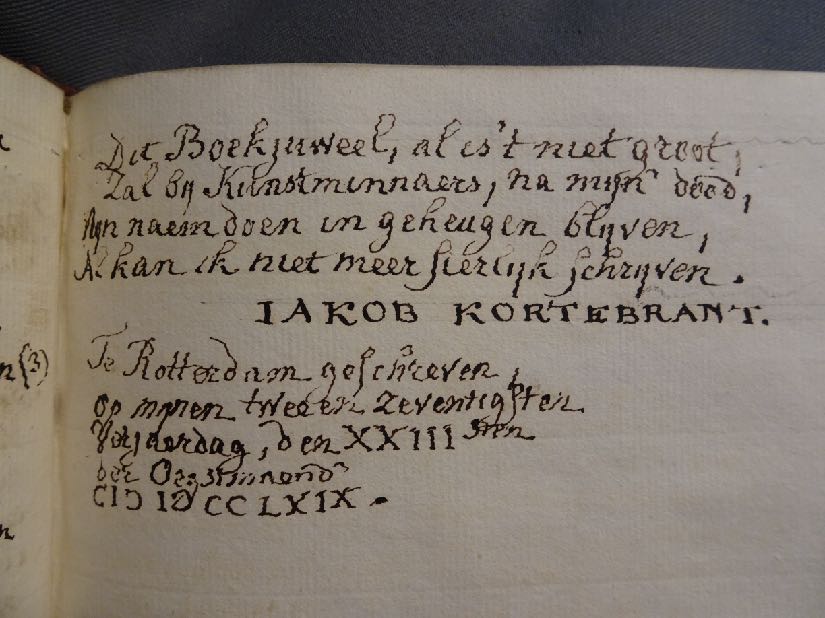

He had the book bound in the present binding, for which, as we read in the final paragraph of his testimonial, he hopes to be remembered into posterity, even though his handwriting is not what it was. Presumably to his lessening eyesight.

'Dit Boekjuweel, al is't niet groot,

Zal bij Kunstminnaers, na mijn dood,

Mijn naam doen in geheugen blijven,

Al kan ik niet meer sierlijk schrijven.’

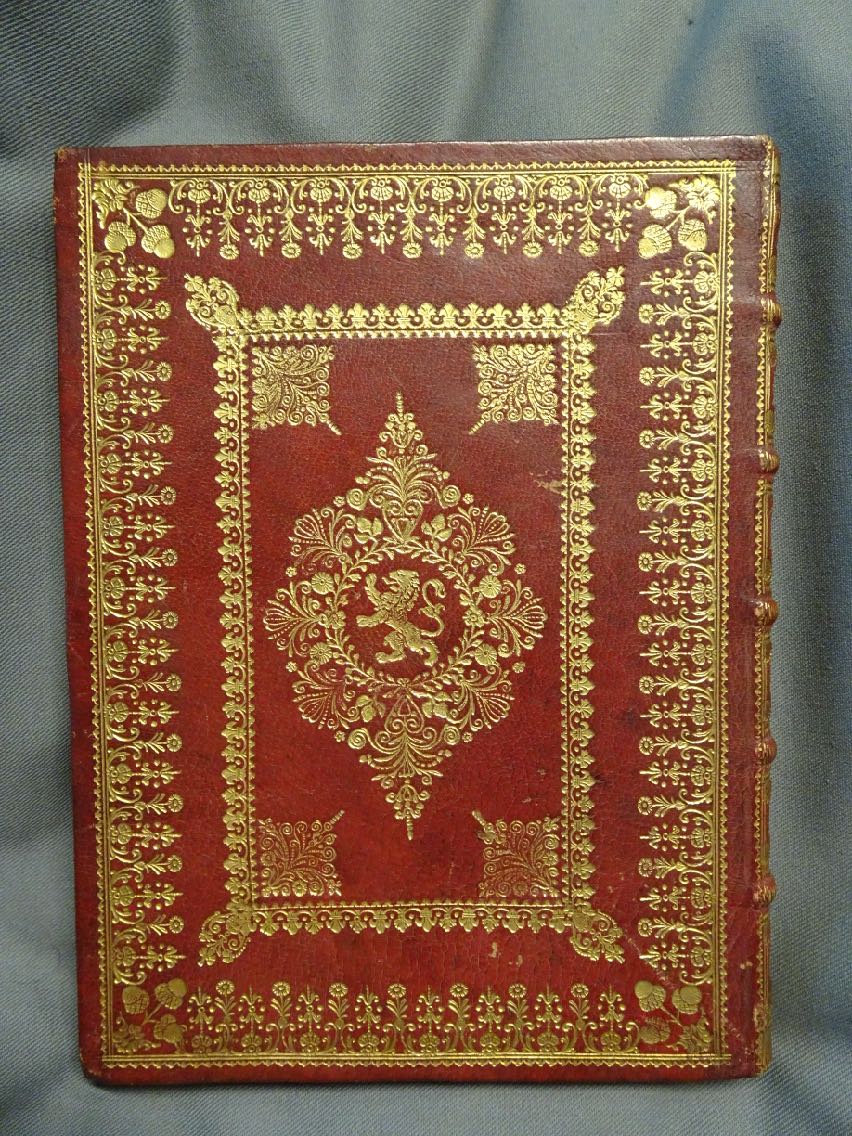

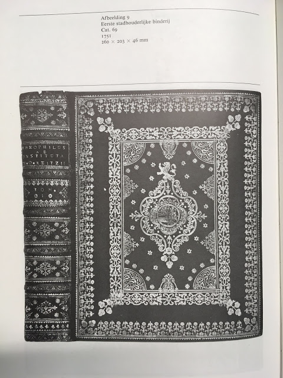

Kortebrant does not identify the binder of Band 1 B 7 in his testimonial, but similarity to the bookbinding below points to his Penninck-Boeck having been bound at the same workshop, the Eerste stadhouderlijke binderij in The Hague. Some of the tools on the binding on Theophilus are also found on Band 1 B 7, the triple acorn cornerpieces, the dentelle frame with standing flowers, and the left-facing lion rampant as part of the centerpiece. The lion rampant also figures in Kortebrant’s coat of arme, the triple acorn tools are iconic for the The Eerste stadhouderlijke binderij. As the most important Dutch 18th century bindery, renowned for luxurious bindings, this bindery derives its name from its most important client, Willem IV (1711-1751), the first stadtholder of the United Netherlands and Prince of Oranje Nassau. Some 180 bindings have been identified to originate from the bindery, all are bound in high quality leather with rich, decorative tooling. Most of these bindings have now found their way into important institutional collections. The Dutch book historian Jan Storm van Leeuwen has inventoried the bindings, their provenance and the individual tools, which has resulted in several in-depth publications by him on the subject. His works are essential reading for any historian studying 18th century bookbinding and its owners.

If, as we think, Kortebrant’s binding was made after 1751, this would be just after the heyday of the Eerste stadhouderlijke binderij 1745-1749, when it produced its most elaborate work. After 1749 the bindings became less innovative, now also meant for the semi-luxurious market, which possibly made them more accessible for customers like Kortebrant.

Theophilus, Paraphrasis Graece. 1751. Storm van Leeuwen 1976. No. 69. Plate 9.

We keep on dreaming

For Kortebrant this copy of the Penninck-boeck was a dream come true. For book historians, his find of a rare printed work between a bundle of old paper is confirmation that there still is a lot out there that we don’t know about, waiting to be found. There are needles in haystacks waiting all over the place, but mostly in the dungeons of all those university libraries. And last but not least, through this publication Kortebrant is remembered, just like he wrote hopefully in his text above.

‘Deze is de beedtenis van braven Kortebrant, Eerwaerdig om zijn’ grijze hairen’. Jakob Kortebrant. 1769. Portrait by Jan Stolker

Provenance

Jakob Kortebrant (c 1697-1777). Poet, artist, writer, historian

Bound for Kortebrant c 1751? - before 1769 by the Eerste stadhouderlijke binderij, The Hague

Presumably part of the Kortebrant sale, Hendrik Beman, boekverkoper te Rotterdam. 8-11-1777

Related binding

The University of Amsterdam owns another copy of the Penninck-boeck: OTM: O 61 9694, which interestingly also lacks the title-page. In both copies the title-page has been added in manuscript by an early owner. In OTM: O 61 9694 the title page has been certified by a notary.

Sales and catalogues Band 1 B 7

Hendrik Beman, Boekverkoper te Rotterdam. 10 November en de volgende dagen, 1777. (Wiersum 1914)

Bibliography

OTM: Band 1 B 7 at the University of Amsterdam

Binding description of Band 1 B 7 at bandenkast.blogspot.com

A.J. van der Aa, K.J.R. van Harderwijk & G.D.J. Schotel, Biographisch woordenboek der Nederlanden. Tiende deel. Haarlem: J.J. van Brederode, 1862. On Jacob Kortebrant: p. 366-368.

Kristian Jensen, Revolution and the Antiquarian Book. Reshaping the Past, 1780-1815. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014. On the washing of paper: p. 153-4.

P.C. Moolhuysen & P.J. Blok (eds.), Nieuw nederlandsch biografisch woordenboek. Leiden: A.W. Sijthoff’s uitgeversmaatschappij, 1911-37. On Jacob Kortebrant: Derde deel (1914), 716-718.

Announcement in the Rotterdamsche Courant. 8 November 1777.

‘Henrik Beman, Boekverkoper te Rotterdam, zal op Maandag den 10 November en volgende dagen op de zaal boven de Beurs verkoopen de nagelaten boeken…van den Heer Jakob Kortebrant, waarvan de catalogus alom te bekomen is.’

Pieter Scheen, Lexicon Nederlandse beeldende kunstenaars, 1750-1880. ‘-Gravenhage: Scheen, 1981. p. 286.

Jan Storm van Leeuwen. De achttiende-eeuwse Haagse boekband in de Koninklijke Bibliotheek en het Rijksmuseum Meermanno-Westreenianum. 's-Gravenhage 1976. p. 55-73. Tooling resembles Band 1 B 7: No. 69, plate 9.

E. Wiersum, ‘Jacob Kortebrant.’ In: Rotterdams Jaarboekje. 1914. Reeks 02. Jaargang 02. p. 54-64.

[Pam van Holthe]