Migrants of the Mind

Barcelona-born bookseller, publisher, and scholar Joan Gili was the son of Lluís Gili Roig, the founder of a publishing house which became known for its elegant books on art and architecture which included Pablo Picasso’s Tauromaquia (1959). Young Gili had a passion for English literature which led to his correspondence with author and broadcaster Clarence Henry Warren who invited him to England in 1933.

Joan Gili (Wikipedia)

At a time of growing political unrest and conflict in his hometown, Gili decided to settle permanently in London in October 1934. He went into partnership with Warren to open a bookshop at no. 5 Cecil Court. Known since the 1930s as Booksellers’ Row, the court had a proud cultural history. It was Mozart’s initial London address where he, arguably, composed his first symphony. In 1863 the first rapid transit railway service was opened in what would become the Barcelona Metro. With the medieval walls knocked down, it opened up the city and was a first step towards expansion.

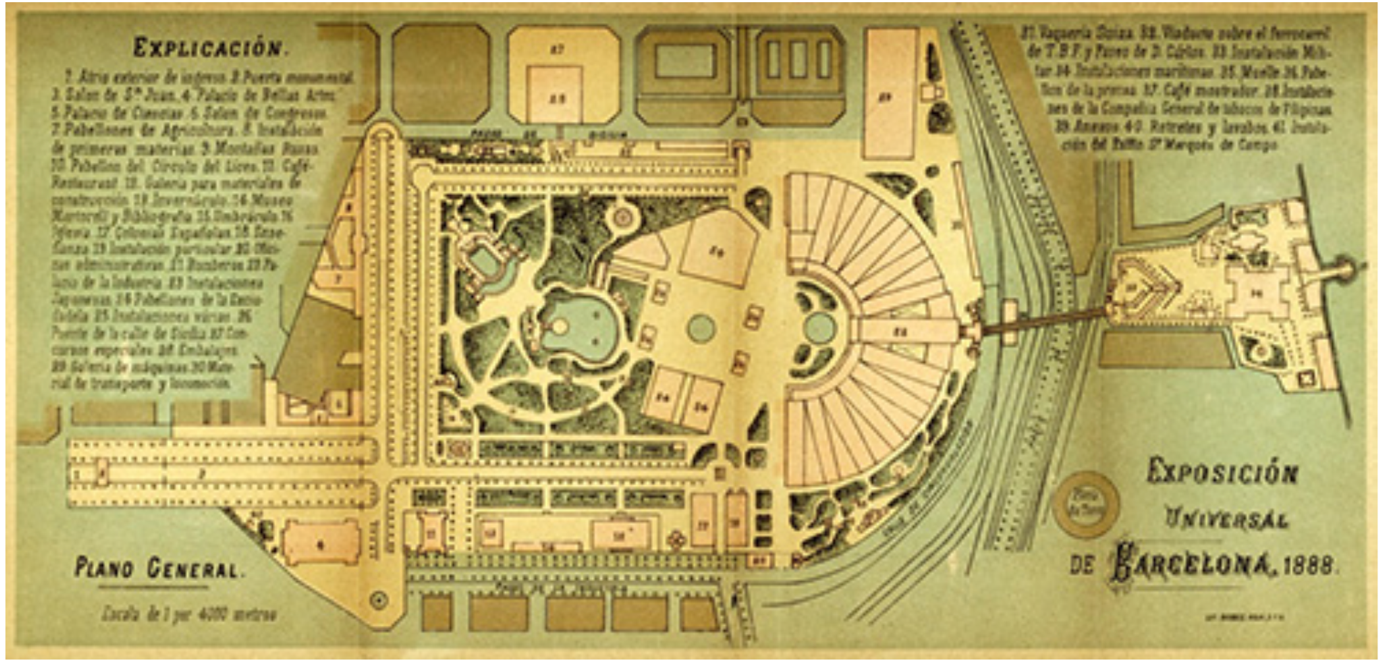

Catalonia developed into Spain’s economic dynamo. Prosperity mushroomed. A self-confident region strove to re-establish its identity by invigorating local culture and language. Barcelona was the engine of change and modernity. The embellishment of the city was ambitious. Having been selected to host the 1888 World Exhibition, the authorities were willing to consider unconventional views of young architects and designers. The period from 1880 witnessed the flowering of ‘La Renaixença’ (the Catalan Renaissance). Identified by a flair for innovation, it was driven by a passion to make Barcelona distinct from Madrid in every conceivable manner.

Juan Valero de Tornos, Guide illustré de l’Exposition Universelle de Barcelona en 1888. De la ville, de ses curiosités et de ses environs. Text de Direction artistique de Juste Simon. G. de Grau et Cie. Barcelona, 1888

Catalan modernism was a coalition across the artistic spectrum, although primarily associated with architecture. Nowhere else in Europe did Art Nouveau leave and equally strong building legacy. The movement was pushed forward by Lluis Domenech i Montaner, director of the Barcelona School of Architecture (where he taught Gaudi). His essay ‘In Search of a National Architecture’ (1878) is a seminal text in the history of the modernism. The challenge was to create a peculiar style that would set Barcelona apart from other world cities. Catalan architecture came to be characterized by a preference for the curve over the straight line, a disregard of symmetry, a passion for botanical shapes and motifs, as well as a return to Arabic patterns and decorations. The style is both colourful and ostentatious. It stands in contrast to the minimalism of modernist construction in northern Europe. In Catalonia, stylistic renewal was a political statement.

The new Catalan style proved perfectly suitable for an Iberian graveyard. Lloret de Mar is an unattractive coastal resort on the Costa Brava. It once was a ship building hub and a centre of trade with the New World. Many youngsters left the town for Cuba or elsewhere in the Americas to make their fortune. On their return, they became known as ‘Indianos’. On 25 April 1898 America declared war on Spain following the sinking of the battleship ‘Maine’ in Havana harbour. Hostilities ended with the signing of the Treaty of Paris in December 1898. As a result Spain lost the last remnants of its colonial Empire - Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Guam, and other islands. The remaining Indianos returned home. Wealthy, cosmopolitan, and often closely related to the Barcelona social elite, they strove to mark their status. They put up the money to create a grand cemetery. In 1892, the project was commissioned to Joaquim Artau i Fàbregas, a disciple of Gaudi. The architect transferred the latest urban planning trends to the interior of the ‘city of the dead’. Avenues, promenades, and squares were lined with modernist tombs and sculptures. The new cemetery opened in November 1901: Catalan funerary art had come alive.

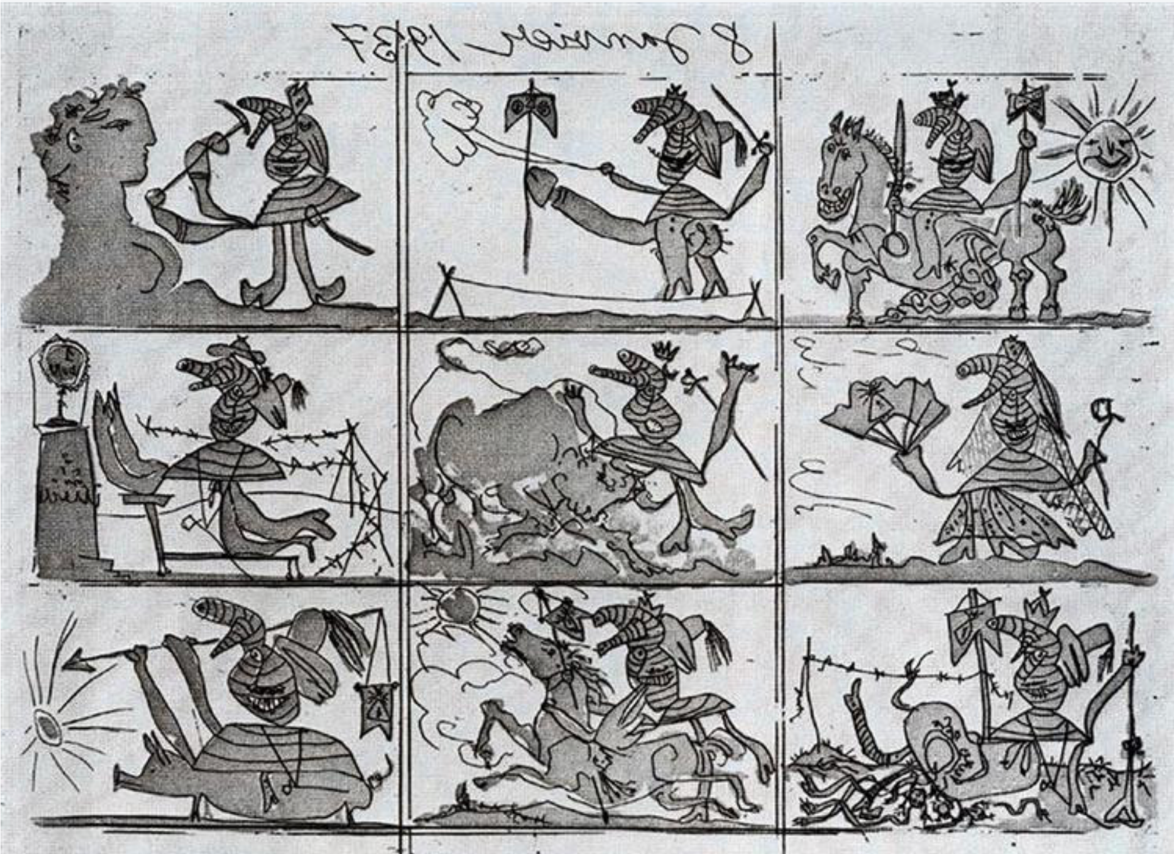

Picasso: Sueño y mentira de Franco (1937

Three decades later death arrived with fury in Catalonia. General Francisco Franco was a devout Catholic, but as commander of Spain’s Foreign Legion in Morocco he permitted his troupes to commit atrocities. In 1936 he led the insurrection against the government. During the Civil War intellectuals, photographers, and artists travelled to Spain offering support to the Republicans. Robert Capa, Langston Hughes, André Malraux, Willy Brandt, Emma Goldman, John Dos Passos, and many others joined the international brigades. Never before had armed conflict been reported in such detail. Ernest Hemingway arrived in 1937 to cover the war. Three years later he completed For Whom the Bell Tolls, the greatest novel to emerge from the battle. Global participation proved fruitless. Following the fall of Tarragona on 15 January 1939, a mass exodus started on the routes leading from Catalonia to France. Some 465,000 people crossed the border. By the end of March, Franco declared victory and received a congratulatory telegram from the Vatican. Once established Head of State, Franco’s propaganda machine praised him as a crusader. Ecclesiastical support convinced him of a divine mission to eradicate liberals and left-wingers from the country. Committed to a policy of institutionalized revenge, Franco rejected any idea of amnesty. As late as 1940, Spanish prisons held political inmates waiting for execution.

El Hogar Español, London

Numerous Republicans sought refuge in Britain. In the late 1930s, after the German blitzkrieg of Guernica, refugees from the civil war began settling in North Kensington, close to the Spanish Republican government in exile which remained active until 1945. Anti-Franco meetings were held at El Hogar Español the Spanish House) in Bayswater. Portobello Road and Ladbroke Grove were centres of Hispanic settlement: London’s ‘barrio Español’. There is some irony here. Known prior to 1740 as Green’s Lane, the name Portobello is derived from Puerto Bello, a harbour town situated near the northern end of the present-day Panama Canal. The port was captured by the English Navy from the Spaniards in 1739 and victory over a maritime rival was met with jubilation throughout the country. George Orwell lived in a grotty flat at no. 22 Portobello Road before he set out to join the Spanish Republicans. In 1938 he would pay Homage to Catalonia.

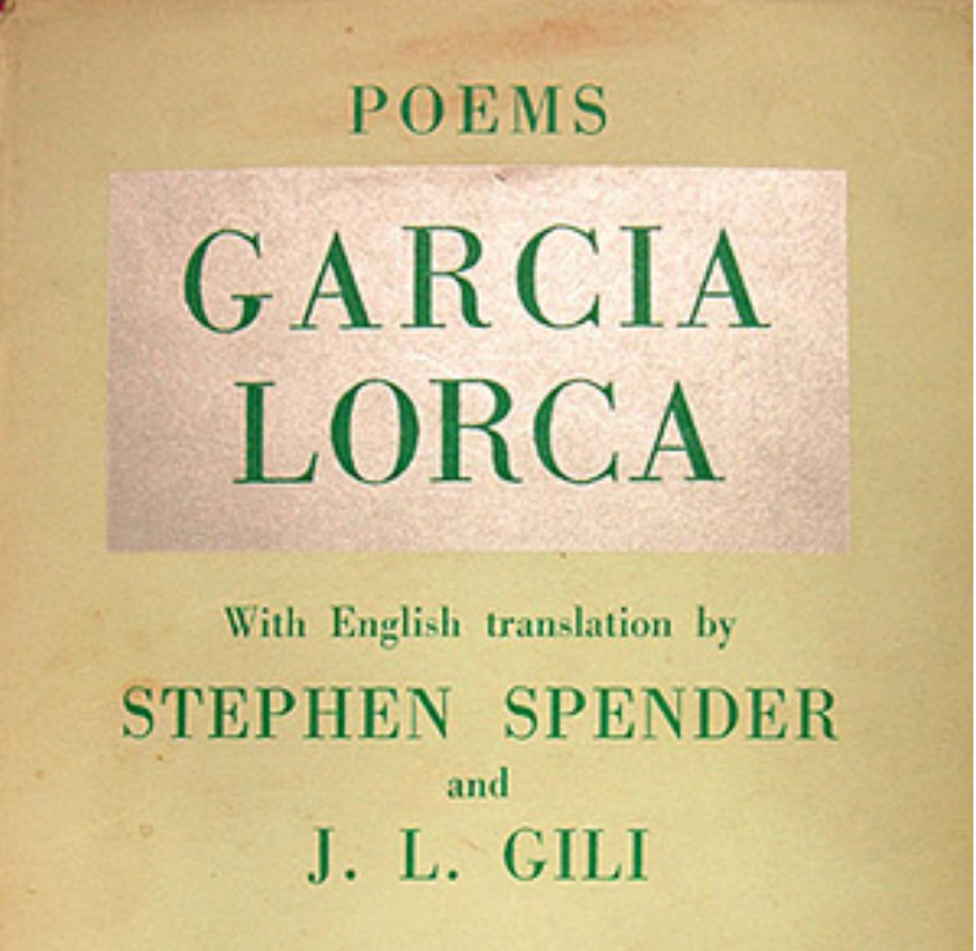

When the partnership with Warren was dissolved Gili, now sole owner, filled the shelves with Spanish textbooks imported from Barcelona. Gili was a mediator between London and Barcelona. From Cecil Court flowed articles and commentaries on English literature, there were also regular ‘Letters from England’, and occasional translations into Catalan of pages from D. H. Lawrence, Katherine Mansfield, T. S. Eliot, and other contemporary writers. He then began to publish on his own account. After meeting Miguel de Unamuno during his visit to England in 1936, he obtained the philosopher’s permission to issue his works in Britain. The first public edition of his Dolphin Bookshop Editions was a collection of Unamuno’s writings selected by Gili himself (1938). This was followed by Federico García Lorca’s Poems, jointly translated by Stephen Spender and Gili, with an introduction by Lorca’s close friend Rafael Martínez Nadal. During the Spanish Civil War Dolphin Bookshop became a hub where supporters of the Republic met and mingled (to the fury of Franco who threatened action against Gili and his family).

Late 1938 Gili secured the contract to transport from Paris to London the fine library of manuscripts and books collected by the French Catalanist Raymond Foulché-Delbosc. This bibliographical coup made him the outstanding Hispanic antiquarian bookseller of his generation. When the Second World War began in September 1939, Gili was registered as an alien in London. Cecil Court seemed a dangerous place to keep priceless books and manuscripts, and the collection was moved to Cambridge first, and from there to a Victorian mansion in Fyfield Road, Oxford. Having settled there, Gili again took pleasure in hosting numerous Spanish Republican exiles.

On 29 July 1940 a National Council of Catalonia was created in London demanding self-determination for the region within a federal Spain. Gili actively promoted the cause by publishing the first edition of his Catalan Grammar in 1943, when the language was banned by Franco’s fascists. In 1954, Josep Maria Batista i Roca conceived the idea of an Anglo-Catalan Society, of which Joan Gili was a founding member and later President. He became known as the ‘unofficial consul of the Catalans in Britain’. Of the seventy-three titles published under the Dolphin imprint between 1936 and 1996 no fewer than twenty-five were Catalan works, forty were Spanish or Latin-American, five were on art, and three were English works. Joan Gili died in Oxford in May 1998, a passionate Anglo-Catalan to his very last day. Critics of immigration fail to understand that it is perfectly possible for an exile to integrate into a host society without sacrificing one’s identity. In fact, those who succeed in doing so tend to be the most creative and productive of newcomers. At best, resettlement is an extension, not a reduction of individuality.

The age of political muscle during the 1930s led to artistic suppression. The tragedy of modernism became evident with the expulsion of writers and artists from their native countries; and with the migration of books and works of art to be safeguarded from the burning eyes of zealots. During Franco’s regime, modernist ideas were perceived as a threat to the country’s moral fabric. The authorities censored all writing that was at odds with its political and religious stance. Literature went into exile. In Britain, Joan Gili had promoted Spanish/Catalan modernism both as a publisher and a translator of Lorca. His son Jonathan Gili, a documentary film-maker and small-press publisher, was a collector of Iberian printed ephemera. He rescued many first editions and rare examples of Art Deco style in print form. In 2014, a decade after his death, Cambridge University Library acquired seventy titles from his collection. It is a tribute to the Gili family that some of their exiled books - migrants of the mind - have found a niche in one of the world’s prominent libraries.

[Jaap Harskamp]