Creation versus Invention: Royal Academy (London)

The word ‘individualism’ was coined in the aftermath of the French Revolution. To many authors and thinkers on either side of the political spectrum, individualism was a dangerous idea. It implied the disintegration of social solidarity and the collapse of communal purpose. Leading to fragmentation, it threatened the stability of government and undermined the affairs of state. Man for and by himself is in permanent conflict with all others and, as a consequence, society pulverizes into a chaos of elementary principles.

Eugene Delacroix. La Liberté guidant le peuple. 1830 (Wikipedia)

During the tumultuous years between 1789 and 1815, European culture was transformed by revolution, war, and ideological conflict. Driven by the Enlightenment, the stage was set for dramatic political and economic change, whilst religion was pushed into a corner. European man, like August Strindberg’s Axel Borg, got rid of the megalomania of Christianity. He considered himself a person who was responsible for and in control of his destiny. The Age of Reason, with its emphasis on rational inquiry to achieve growth (‘perfectibility’), undermined the religious foundation of the political order. Voltaire and Diderot in France, like David Hume and Jeremy Bentham in Britain, explored the non-religious bases of power. Freedom of expression was intimately interwoven with civil liberties. The ground was being prepared for democracy to emerge.

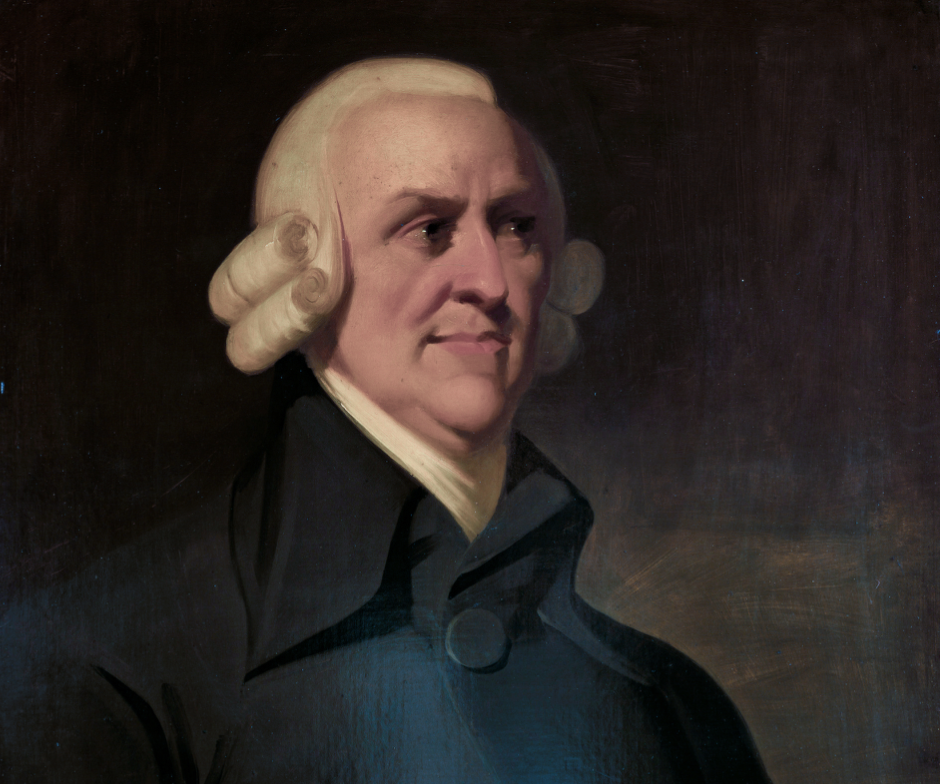

Adam Smith. Posthumous portrait, ca 1800 (Wikipedia)

Economically, efforts to maximize production precipitated a re-organization of the workplace. In The Wealth of Nations (1776) Adam Smith introduced the concept (and phrase) of ‘division of labour’, but he warned of its potential danger. If work was reduced to mechanical manipulation, the operative would be a mere extension of the machine. He stressed the importance of education to avoid the ‘stultification’ of workers. Adam Ferguson acknowledged the benefits of the system, but he too sounded a warning. While Smith feared the effect of specialization on the individual, Ferguson argued that excessive division of labour might loosen the ties that bind society together and initiate a process of disintegration. In spite of such warnings, fragmentation proved unstoppable - both in manual and academic work. Goethe had already complained that the sciences were in the process of being pigeon-holed. A multitude of disciplines prevented the forming of an integrated world-view. Dealing with splinters of reality, sight of the bigger picture was lost. The knowledge of parts may increase, but the whole retires into darkness.

Henry Fuseli, by James Northcote (Wikipedia)

Traditionally the primary meaning of the term ‘art’ was man’s skill of making things, be it a chair, a painting, or a tapestry. The Romantics prompted the divorce between ‘techne’ and ‘ars’. The artist took pride in his newly gained independence from which he derived grand ambitions. Art came to be regarded as individual expression, inspirational in origin. Traditionalists expressed concern about such an extension of the ego. In 1801, Henry Fuseli issued his Lectures on painting, delivered at the Royal Academy in which warned that the terms invention and creation should not be confounded. Creation is ‘admissible only when we mention Omnipotence: to invent is to find: to find something, presupposes existence somewhere, implicitly or explicitly, scattered or in a mass: nor should I have presumed to say much on a word of a meaning so plain, had it not been, and were it not daily confounded, and by fashionable authorities too, with the term creation’.

Alphonse de Lamartine by François Gérard (Wikipedia)

Such reservations fell on deaf ears. Poets and artists claimed to follow the method of the Divine Maker: ‘Le beau, c’est le rêve de l’artiste achevant par l’imagination l’oeuvre de Dieu’, Alphonse de Lamartine boasted in 1858. The word creativity should no longer be used exclusively with the Creator in mind. Artists demanded their share of creation, they aimed at rivalling God. Such claims were made in the early phase of Romanticism, but they lasted throughout the age of modernity albeit in more modest terms. The aspiration was summarized by Polish writer and artist Bruno Schulz in The Street of Crocodiles (1933): ‘We have lived for too long under the terror of the matchless perfection of the Demiurge … For too long the perfection of his creation has paralyzed our own creative instinct … We wish to be creators in our own, lower sphere; we want to have the privilege of creation, we want creative delights, we want - in one word - Demiurgy’.

Victor Hugo by Nadar (Wikipedia)

The artist’s intent to trust the uniqueness of his personal talent would undermine traditional art education. Academies were attacked for restricting students and stifling their individuality. Inevitably, the quest for originality led to fragmentation. To indicate a splintering of the artistic domain the label ‘cultural anarchy’ became the dominant metaphor. Initially, artists took delight in this tag. To young French romantics creativity meant confrontation. The battle against Classicism was fought out on the stage and the 1830 production of Victor Hugo’s Hernani marked the triumph of Romanticism. Leading up to this victory, a number of artists in support of Hugo took pride in the state of chaos that had been created. Our revolution is in full swing, Benjamin Constant wrote in 1829. It may be anarchy for now, but ‘cette anarchie est une transition nécessaire entre le passé qui s’enfuit et l’avenir qui arrive’. In November of that same year Charles Magnin overviewed the literary domain and witnessed a state of anarchy that seemed to undercut traditional theories and convictions. Freedom creates fragmentation, Magnin claimed, which is both legitimate and beneficial to the arts.

Quatremère de Quincy (Wikipedia)

By contrast, defenders of the status-quo - such as the influential classicist Quatremère de Quincy - predicted that the undercutting of artistic unity would lead to confusion and disarray. One of their prime concerns was the perceived decline of the art of building. Ever since the arts had become divorced from architecture, they had gone their separate ways developing into independent branches of creative endeavour. This particularization caused a detachment from social purpose. The twin demands of individuality and originality dealt a final blow to stylistic continuity. The artist, cut off from the community of faith, stood alone and was made slave to the ‘anarchy’ of his personal emotions. Subjectivity was the hallmark of disintegration. Culture became dismembered and scattered.

The controversy between romantics and classicists signalled elements of future modernist developments: resistance against formalized education, breakdown of authority, and the confrontation between experimental and established art forms. In a society in flux youth seemed to be called upon to play a decisive role. In April 1778, Samuel Johnson had complained about the breakdown of ‘subordination’ and the ‘relaxation of reverence’. With an emerging request for modernity, the world was claimed by the rebellious. Today a desperate struggle is being carried on with the old man who is trying to stifle youth, Kazimir Malevich wrote in ‘The question of imitative art’ (1920). Today we are ‘witnessing one of the usual mistakes of the old, which does not comprehend the movements of new life; today the old men are striving to ensure that there may never be another spring’.

Kazimir Malevich, Self-Portrait (Wikipedia)

Modernism was a culture of the young, a celebration of the new. Novelty however, like youth, is of brief duration. It is art’s most perishable feature. The nineteenth century had transported the doctrine of progress into the domain of literature and art. Baudelaire called the idea of cultural advancement ‘une absurdité gigantesque’. Architect Augustus Welby Pugin, designer of the interior of the Palace of Westminster and pioneer of the Gothic Revival in Britain, made it his mission to ‘pluck from the age the mask of superior attainments so falsely assumed’. The hubris that modernism was a ‘final state’ in whose presence all preceding art was judged mere preparation (just like youngsters today see the introduction of Google as the beginning of history) proved to be a myth. Art refers to existential concerns that are fundamental to the human condition. In different times answers will vary and are posed in new aesthetic forms. They form part of an ever enlarging human repertoire from which new generations draw their own particular experience. The ‘March of Intellect’ does not stop: creativity is synonymous with movement, it is fluid and flowing, always sapping the rigidity of stagnation. Movement does not indicate direction - let alone, a forward course.

[Jaap Harskamp]