Beyond the religious divide: Rubens and Mayerne in London St Martin’s Lane (Covent Garden)

Peter Paul Rubens was a painter with a Baroque brush. He was admired by his contemporaries as the creator of dramatically charged and sensual scenes. As a person, by contrast, he established a reputation for tact and discretion. His genius opened doors to European monarchs and statesmen. He offered the perfect profile as a covert diplomat, his art providing cover for politically sensitive activities.

In 1629 he was sent to London by Philip IV on a (nearly) ten month mission to pave the way for a peace treaty between Spain and Britain. Charles I took this opportunity to conclude the details of a substantial commission for the ceiling paintings at Banqueting House, Whitehall Palace, in memory of his father James I. The nine canvases were produced at Rubens’s factory-like studio in Antwerp and eventually installed in 1637. For his diplomatic efforts and artistic skills, he was knighted by both monarchs.

Although eager to return to Antwerp, his long stay in London was productive from a creative point of view. Having brought his brushes with him, he accepted a number of commissions, including a three-quarter length painting of Thomas Howard, 2nd Earl of Arundel, whose collection of classical sculpture was accommodated in a mansion on the Strand.

Another and more intimate work shows the wife (Deborah Kip) and children of Middelburg-born Balthazar Gerbier, probably painted at York House where the latter was employed as keeper of and agent for the outstanding picture collection of George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham.

Mingling with London’s diplomats, it was inevitable that Catholic painter Rubens would meet Protestant physician and polymath Theodore de Mayerne. It turned out to be a happy meeting of minds – in spite of religious differences.

On his penultimate day in London, Rubens paid an unauthorised call to the Chelsea residence of Albert Joachimi, Ambassador of the United Provinces in London. During this visit he made an unsuccessful plea for a truce in hostilities between the Netherlands and Spain. It seems likely that this meeting between two opponents was facilitated by Mayerne who, that same year, had married Joachimi’s daughter Elisabeth in Fulham.

Theodore de Mayerne was born at Geneva on 28 September 1573 and was named after his god-father, the reformer Theodore Beza. He studied medicine at Montpellier, before being appointed physician to Henry IV. When his Protestant background barred his career advancement, he moved to London in 1611.

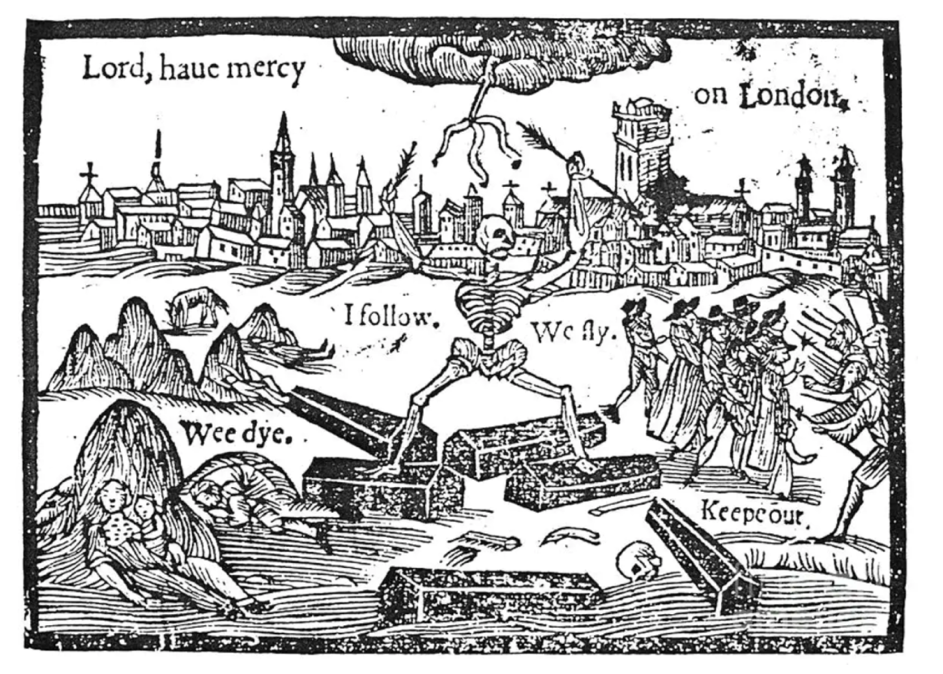

Having settled at St Martin’s Lane, he was appointed Physician-in-Ordinary to the Stuart court. He kept a record of the many afflictions and final illness of James I (a cadaverous appearance, weak legs, swollen feet, arthritis in the joints, sore lips, and bad breath, the King repelled those close to him by hiccupping and belching). Charles I kept Mayerne in his post requesting a report from him on measures to prevent a plague epidemic. During the turmoil of civil war, Mayerne balanced himself between Parliamentarians and Royalists and he survived Oliver Cromwell’s rule unharmed.

At a time that the profession of physician in England was barely developed, Mayerne was part of a European medical clerisy, a group of elite practitioners who, writing and conversing in Latin, pushed medicine away from preachers and quacks. Cholera does not attend church, the plague has no pulpit. Disease is the great equaliser.

Mayerne was among the first to apply chemistry to the compounding of medicines. He experimented with drugs that were not recommended in the Pharmacopoeia Londinensis compiled in 1618 by fellows of the Royal College of Physicians. His clinical reputation kept them from taking action against his ‘unorthodox’ approach of prescribing chemical remedies.

Mayerne’s interest in the structure and properties of substances extended into other domains of activity. He applied scientific methodologies to the study of artistic techniques (and pondered how painting could benefit from the development of chemical knowledge). The British Library holds the splendid ‘Mayerne manuscript’ (MS 2052, acquired by Hans Sloane, and catalogued as Pictoria, sculptoria et quae subalternarum atrium). Dated between 1620 and 1646, the manuscript contains notes on the making of pigments, oils, and varnishes; the preparation of surfaces for painting; and the repair and conservation of works of art.

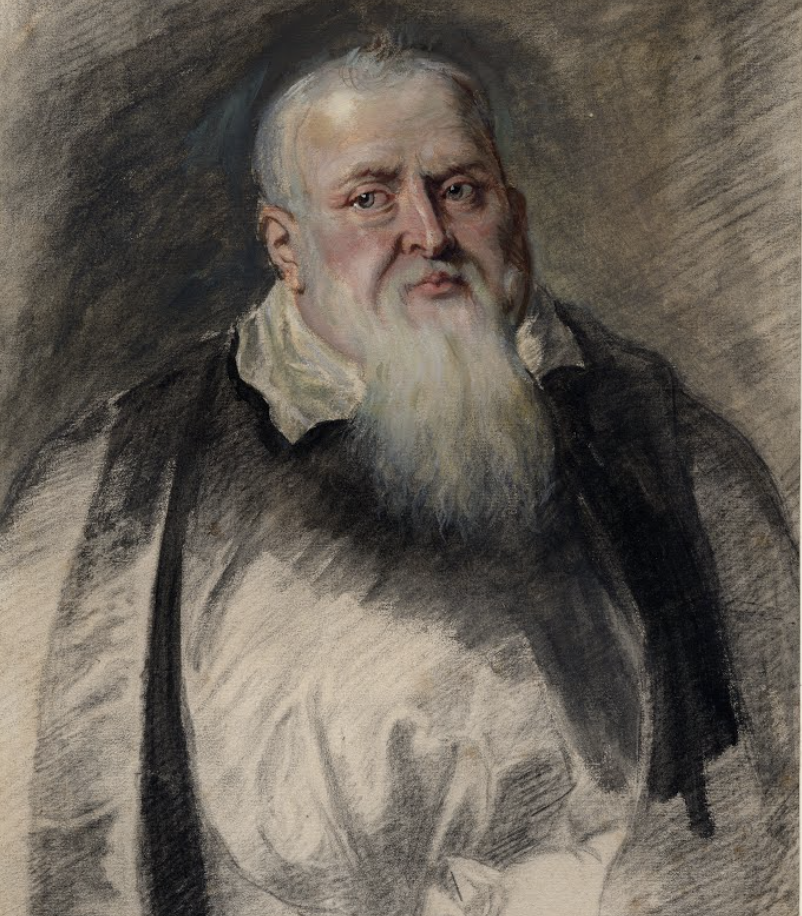

Mayerne was in personal contact with Dutch and Flemish artists who had made London their home and involved them in his research. He interviewed Anthony van Dyck and it has been suggested that his research into the properties of pigments helped fellow Swiss immigrant Jean Petitot to reach the perfection of his colouring in enamel. Considering all this, it is not suprising that Mayerne was keen to meet great Rubens during his London mission. The British Museum holds a sketch in black chalk which Rubens later used for his Mayerne portrait (executed in Antwerp in 1631).

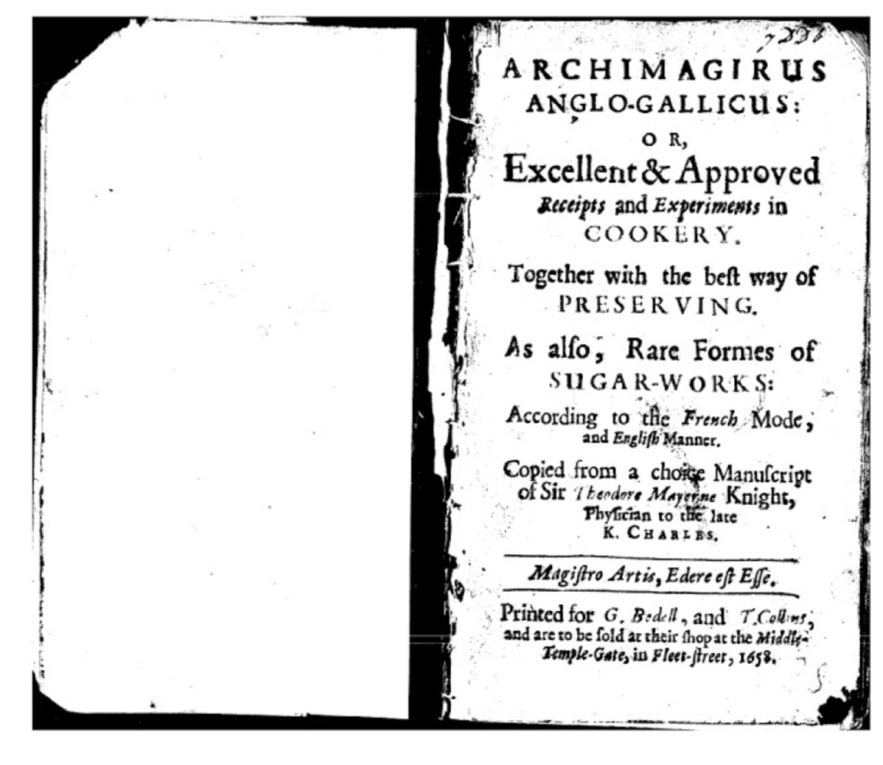

Like a number of medical men in history, Mayerne was also interested in the art of cooking (to the Romans, the word ‘curare’ signified to dress a dinner as well as to cure a disease). Mayerne’s 1658 cookery-book bears title Archimagirus Anglo-Gallicus[The Anglo-French chef].

As he was regularly invited to gatherings organised by the Lord Mayor, he named his first recipe ‘A City of London Pie’. This gastronomic tour de force contains the following ingredients ‘eight marrow bones, eighteen sparrows, one pound of potatoes, a quarter of a pound of eringoes, two ounces of lettuce stalks, forty chestnuts, half a pound of dates, a peck of oysters, a quarter of a pound of preserved citron, three artichokes, twelve eggs, two sliced lemons, a handful of pickled barberries, a quarter of an ounce of whole pepper, half an ounce of sliced nutmeg, half an ounce of whole cinnamon, a quarter of an ounce of whole cloves, half an ounce of mace, and a quarter of a pound of currants. When baked, the pie should be liquored with white wine, butter and sugar’.

It is hardly surprising that, in late life, obesity made him immobile. Ironically, the cause of his death in March 1655 was attributed to consuming bad wine at the Canary House tavern in the Strand.

[Jaap Harskamp]